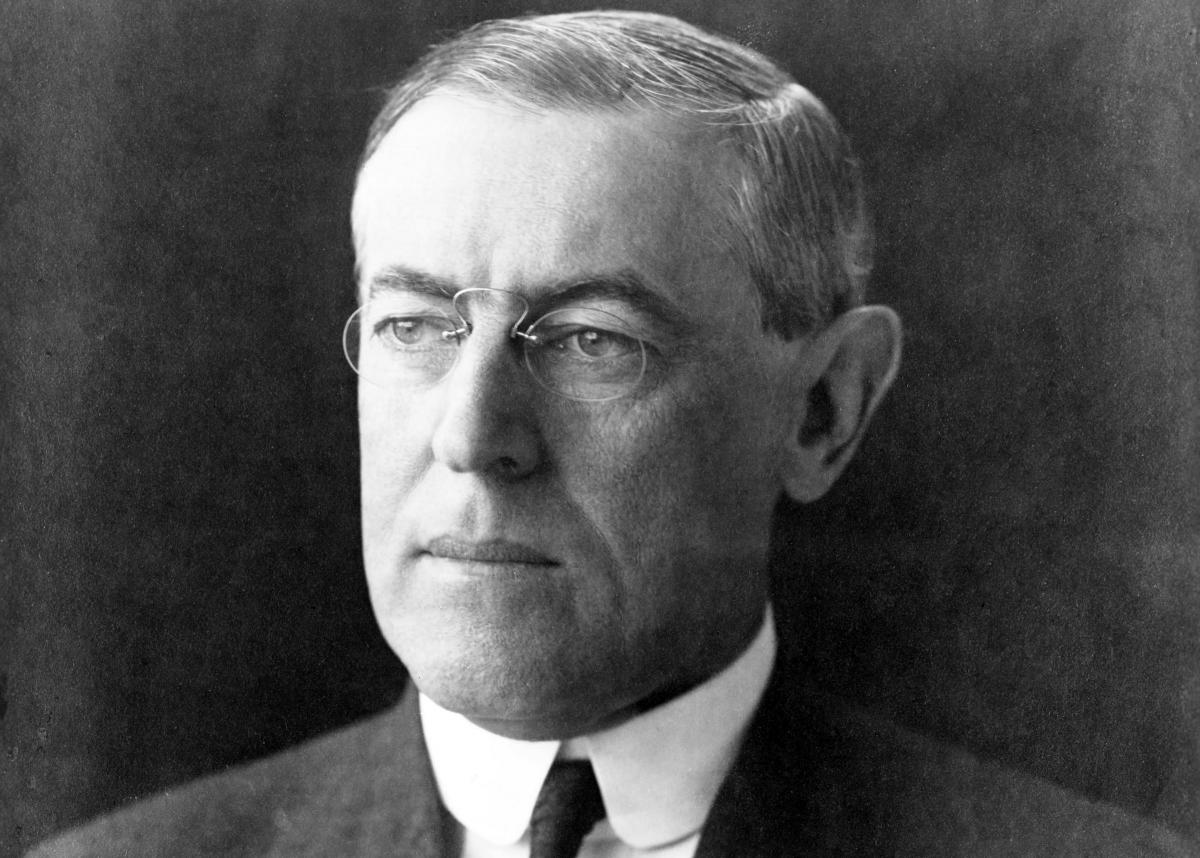

I WAS interested to read the article in Monday’s National regarding Princeton University’s decision to retire the name of Woodrow Wilson from two of its institutions (US university to remove name of racist president, June 29).

Despite being a progressive president, and winning the Nobel Peace Prize, his name will be expunged from the very university of which he became president, as a consequence of his racist views.

The logical conclusion of this is that other worthies whose names are linked to past misdeeds can expect their names to be similarly purged.

READ MORE: Princeton to remove name of racist president Woodrow Wilson

It will be intriguing to discover what the USA will rename Washington (national capital and state), Madison (capital of Wisconsin) and Jefferson City (capital of Missouri), as all these presidents are associated with racial inequality. The first two were multiple slave owners and although Thomas Jefferson was a lifelong abolitionist he believed the black man to be racially inferior and he espoused gradual emancipation, much like our own Henry Dundas.

Closer to home we have a number of streets in Glasgow that will require revision, most notably our weel-kent Buchanan Street.

Would it not be preferable to educate on the iniquities of these obsolete beliefs rather than eradicate them from history? In many cases these dignitaries are feted for the good they achieved in their lifetimes, not the bad. Remember nobody is, or ever will be, perfect.

Ian Mackay

Hamilton

I WAS gratified to see Martin Hannan’s article reassessing Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. For too long he has escaped proper scrutiny and been hailed as a great president who championed internationalism and progressive domestic policies. Since 1948, regular polls have been conducted on how Americans (or at least historians, academics and political commentators) view their presidents. Wilson has consistently been located in the top quarter, most recently sitting at number 11 out of 44.

Wilson’s much-vaunted self-determination-of-nations doctrine, which shaped the terms of the post-World War One Versailles Treaty, may have seemed liberating and democratic. However, since the guiding principle behind the setting of borders and the defining of nationality was race, this effectively created a tinderbox of divisions, resentments and hatreds across Europe, just waiting for those acolytes of racial superiority, fascists and Nazis, to come along and set light to it. The Treaty of Versailles was a staggeringly bad arrangement and, it can plausibly be argued, was a significant cause of World War Two.

Wilson has historically been portrayed as a liberal politician, a progressive Democrat who upheld the interests of the powerless. Less often is he associated with intolerance and injustice. Born into a slave-owning family in Virginia in 1856, he remained a dyed-in-the-wool segregationist all his life. He saw segregation not as a problem, but as a positive good. When a delegation of black professionals met him in 1914 he said to them, “Segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen.”

Wilson dealt with the "negro problem" while in office largely by ignoring it, but when he did act, he retarded Civil Rights. In 1912, federal government agencies had been integrated since the late 1860s. Many African-Americans held jobs at all but the highest levels. Within a short time, Wilson authorised his departmental chiefs to drop this policy. Cafeterias and toilet facilities were segregated, while screens were erected in some offices to separate white from black workers. Many black federal employees were sacked and the remainder found it increasingly difficult to achieve promotion.

During World War One, Wilson permitted discrimination in the armed forces greater than during the Civil War. The US Navy completely barred black Americans, while the Army allocated most of its 400,000 volunteers to labouring duties. In the 1919 Paris victory parade, Wilson vetoed the participation of black US servicemen.

Wilson’s sympathetic attitude towards white supremacy was further illustrated when he approved the screening in the White House of Birth of a Nation, DW Griffith’s racist portrayal of the post-war south and heroic depiction of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had been supressed by the military in the 1870s, but almost immediately after the film’s release it was re-founded, and by the 1920s it had 4,000,000 members. The film’s captions included quotations from Wilson’s writings, taken from his book A History of the American People, where he displayed a jaundiced view of black participation in reconstruction and a rose-tinted view of the Klan. A flavour of his prose:

"The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation to rid themselves of the intolerable burden of governments sustained by the votes of ignorant negroes … governments whose incredible debts were incurred that thieves might be enriched … There was no place for the men who were the real leaders of the southern communities … shutting white men of the old order out from the suffrage … It threw the negroes into a very ecstasy of panic to see these sheeted 'Ku Klux' … and their comic fear stimulated the lads who excited it … until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, an 'Invisible Empire of the South', bound together to protect the southern country from some of the ugliest hazards of a time of revolution."

It seems a wonder that it took Princeton University so long to disown such a divisive man.

Dr David White

Galashiels

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel