ALAN Riach: Sorcha, could you tell us first about your earliest encounters with Alasdair Gray and his work? Where did you first meet him? How did you come to read his books? And was it the writing or the art that caught your attention primarily?

Sorcha Dallas: My working relationship with Alasdair goes back to 2008 when I was running my commercial gallery – but my interest began many years before when I was studying at Glasgow School of Art and reading Lanark. Reading Lanark was a bit of a rite of passage when at art school and it shaped my and many of my peers’ thinking about what it was like to live in a place imaginatively.

I was also aware of how his work permeated the west end of Glasgow, where I’ve lived most of my adult life. I’d encountered his murals in the Ubiquitous Chip restaurant and bar. I’d bought his carefully designed books in what was then John Smith’s Byres Road bookshop and I had snatched glimpses of his distinctively styled paintings through tenement windows.

In 2007, I discussed with a friend, Neil Mulholland, that I was keen to make an approach. Neil knew Alasdair and suggested I write a letter, which I did, and a few days later received a beautifully hand-written one back inviting me round to his flat. I remember the nervous walk going up Observatory Road, which quickly dissipated when he greeted me in his dressing gown and slippers!

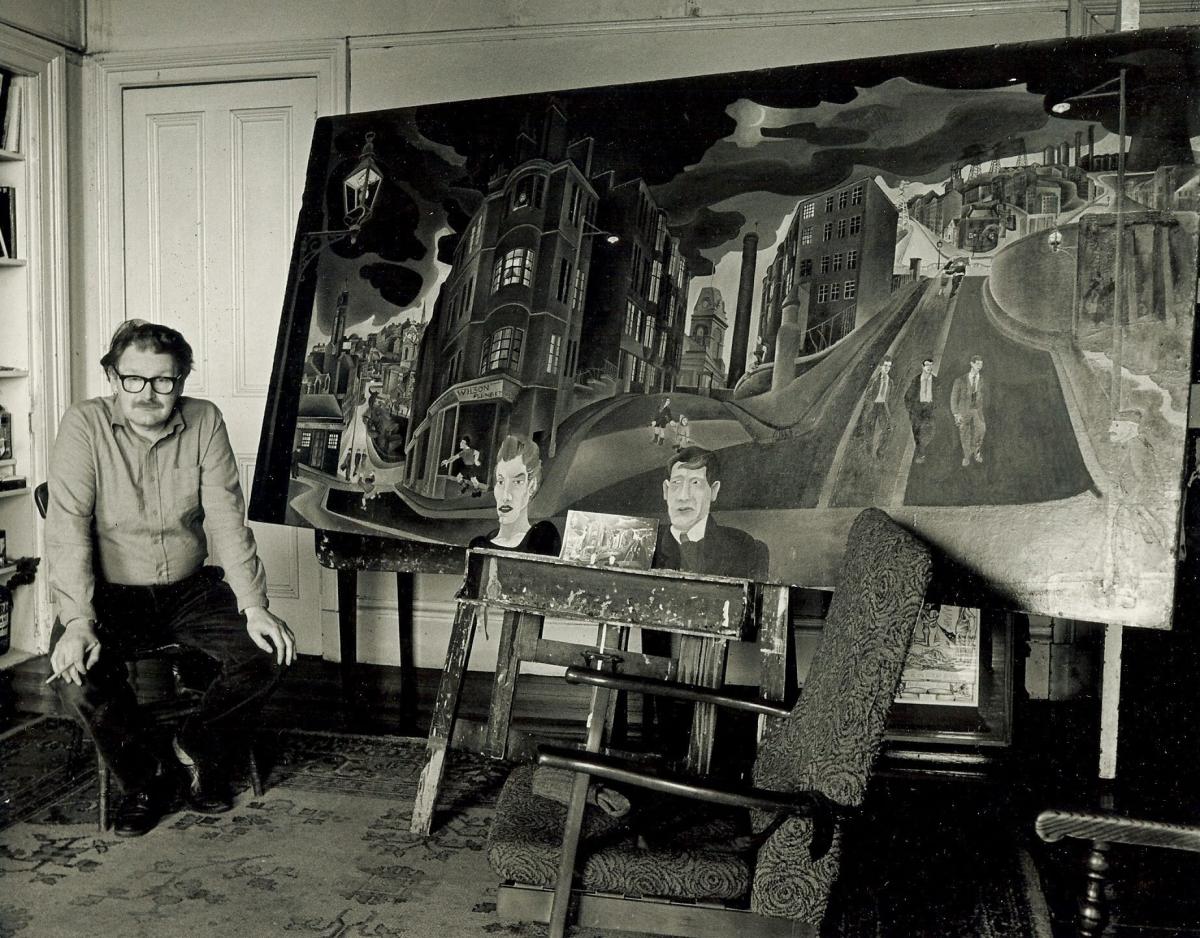

He welcomed me into his room and my breath was taken away by what I encountered – books, artworks (in various states of completion), manuscripts, letters, ephemera, the artist’s materials. It was a rich, welcoming environment and I was always grateful to be able to spend time within it.

We chatted about art and as I was building up to ask him about working together (possibly realising my nervousness) he interjected and said: “I would like you to be my dealer!” And there began one of the most significant and life-changing relationships of my adult life.

Alan: You looked after Alasdair’s work and co-ordinated his exhibitions through the later years of his life. Could you tell us a little about the challenges this presented? And the triumphs?

Sorcha: Trying to map and record Alasdair’s expansive practice was a bit like trying to nail jelly to a wall! It had a life of its own.

I quickly realised I would never be able to fully record or even to know what he’d done. He was generous and often works were given to friends, or were used to pay for meals or for support. Trying to fully define what’s out there is and was an ongoing challenge.

From the start, I was aware of Alasdair’s expansive visual practice and how this had never been formally accessioned. I was prompted to start to look at this in relation to his visual archive as he was working on his book A Life in Pictures with Canongate so I started working with him at a good time as he was already trying to capture what he had created.

I helped him collate and locate details of works he wanted to feature and created a system which detailed further information on them such as year, medium and owner. This then became a starting point to try to map his wider works, beginning with the ones he had at home and then expanding to take into account works in public and private collections.

This was invaluable to work from when planning The Alasdair Gray Season, a city-wide series of exhibitions and events that I devised for Glasgow Museums in 2014-15, the central show being the retrospective “From the Personal to the Universal” at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

Over the years we’ve made public calls for works we’re keen to locate, more often than not these searches flag up more unrecorded works! That was challenging but there’s a value in this way of working. Alasdair’s generosity meant that many people had a direct connection to him and his work via a drawing or a signed book and that makes his work important on such a fundamental level.

I see this as a strength, moving forward. There’s such a rich community around him offering insights into his personality and creativity.

Alan: How was that reflected in your own work, to ensure he was represented in the art galleries?

Sorcha: As his gallerist, I supported his visual practice through creating a network of international galleries, collectors and curators, enabling his work to be included in key exhibitions such as the British Art Show 7; “Gray Stuff” at The Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh; “Poor. Old. Tired. Horse.” at the ICA, London, and through acquisitions into public collections including the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, the Arts Council of England and the Tate.

I managed commissions including SPT Hillhead, De Rosa album cover and Pringle of Scotland jumper commission.

Alan: So many galleries, so many commissions, so many different audiences, and so many ways of seeing. It’s as if it were a public demonstration of that elusive quality of his multi-faceted art – as artist and as writer – that seems essential in everything he did.

I think there’s one key moment in Lanark where this is described. It’s when the aspiring artist Duncan Thaw sets out to draw the Blackhill Locks in the canal, just north of Glasgow and not far from where the Alasdair Gray Archive is held, in the Whisky Bond: “He knew how the two great water staircases curved round and down the hill, but from any one level the rest were invisible. Moreover, the weight of the architecture was best seen from the base, the spaciousness from on top; yet he wanted to show both equally so that eyes would climb his landscape as freely as a good athlete exploring the place.

“He invented a perspective showing the locks from below when looked at from left to right and from above when seen from right to left; he painted them as they would appear to a giant lying on his side, with eyes more than a hundred feet apart and tilted at an angle of 45 degrees.

“Working from maps, photographs, sketches and memory his favourite views had nearly all been combined into one when a new problem arose.”

This “new problem” is how to depict people in this landscape. Realism is a term bound up with the matter of perspective, and it is a key idea in the transition from 19-century realism to modernism.

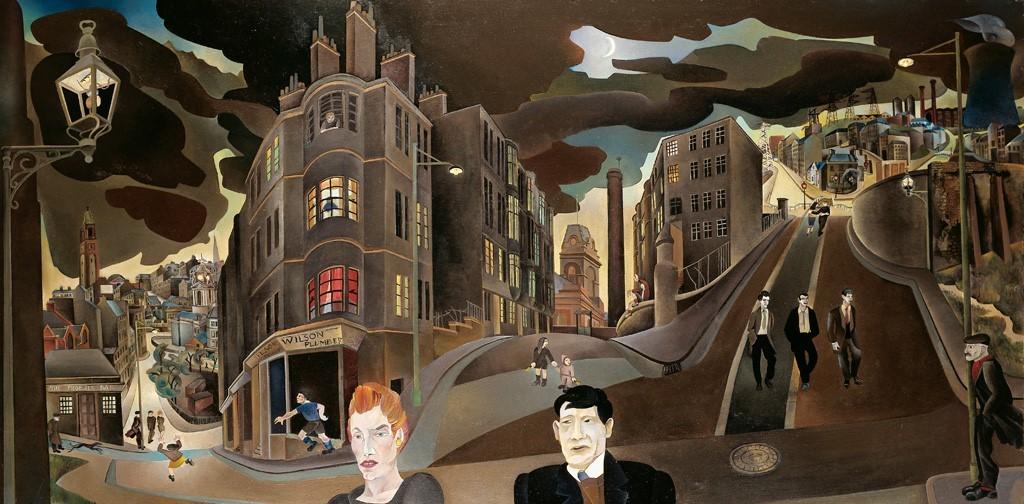

Here Gray dramatises the problem by bringing it to his fictional character. This is something Gray himself experienced, as is evident in his drawings of the Blackhill Locks, c.1950 which are in his book, A Life in Pictures and the painting, “Cowcaddens Streetscape in the Fifties” (1964).

And I think this is one of the most distinctive aspects of Gray’s work: he imagines people in their landscapes, cityscapes, places, economies, at play, in relationships, and working, in actual jobs. I think I heard a rumour that he was going to call his last work, “Who’s Paying For This?”

He’s a political writer in this very specific sense. He imagines people not only from the inside, as it were, psychologically, in relationships with each other, in families and at work, which every fiction writer does, but he also imagines how they are seen, how they might be seen. I mean, he tries to get you to see them as a giant might see them, on the earth, in the cosmos – or in a world ruled by economic exploitation.

Sorcha: And this is in his portraits too, these are people observed, in their domestic habitats, environments, living rooms, wherever. Those settings have their own economic history, and their own place in the history of fashion and politics and architecture. He opens the world to us.

Alan: He asks you to see people in the structures of an economic monster, dictating their options, affecting their responses, frustrating them or occasionally perhaps liberating them into worlds of possibility. And, too often, foreclosing that possibility.

And he shows how sometimes people can subvert the will of the monster. Consciously or unconsciously, by design or intention or else by fortuitous luck, accidental collision or happenstance.

The fact life is intrinsically dynamic means that things change, will change, or as Edwin Morgan put it, the “supreme graffito” is, “CHANGE RULES”. (You need to change the RULES, but also, CHANGE is what rules us all.) Alasdair Gray is not quite like anyone else in this regard.

In his 1898 Preface to The Nigger of the “Narcissus”, Joseph Conrad says this: “My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel, above all to make you see. That – and no more; and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there, according to your deserts, encouragement, consolation, fear, charm – all you demand – and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.”

The visual metaphor is conveyed with startling urgency. This is compelling prose. The metaphor – “to make you see” stands for to make you understand comprehensively, to see deeply and from every angle, to read the world insightfully and feelingly – is conveyed in slightly awkward English: “My task which I am trying to achieve’ is perhaps a phrasing characteristic of someone who was not brought up a native speaker of English, and yet its strangeness enhances the urgency of the point, as if without artifice, rather with the sense of a dense force willing itself through its own expression.”

Joseph Conrad said he was trying, in all his writing, to make his readers “SEE” but I think that Alasdair perhaps had a more literal sense of the value of that, more than Conrad might have predicted.

Sorcha: And that’s what the Archive is trying to keep going.

Please get in touch to arrange a visit: sorcha@thealasdairgrayarchive.org

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here