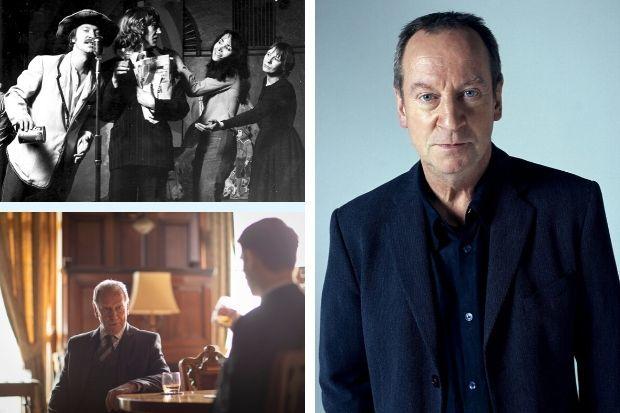

WHAT’S your favourite Bill Paterson moment? Well, I would hazard that, if you’re anything like me, choosing just one will be no easy feat. We’re talking about a man who has worked pretty much consistently – seldom to be found “resting” in acting parlance – for more than 50 years (and counting).

Paterson, 74, made his professional acting debut at the Citizens Theatre in his native Glasgow in 1967. He became a regular among the ranks of the 7:84 theatre company during the 1970s when he toured with the late John McGrath’s landmark play, The Cheviot, the Stag, and the Black Black Oil.

The actor appeared with Sir Billy Connolly in comedy musical The Great Northern Welly Boot Show, and performed in John Byrne’s first play Writer’s Cramp, before joining the much-lauded 1982 revival of Guys and Dolls at the National Theatre in London which broke box office records.

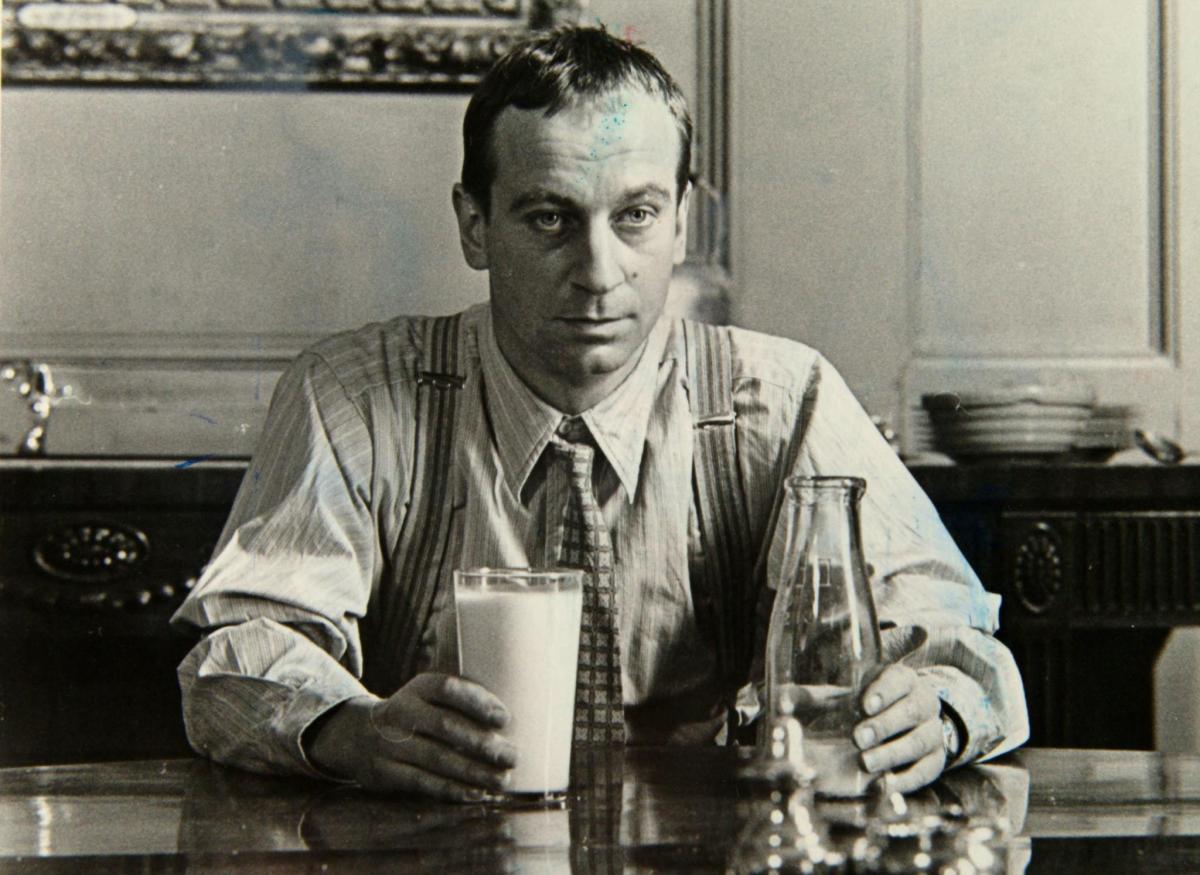

Among his early film roles was playing radio DJ Alan “Dicky” Bird in the Bill Forsyth directed-and-written comedy, Comfort and Joy, as well as parts in the Oscar-winning The Killing Fields and A Private Function alongside Michael Palin and Maggie Smith. He’s long tapped into the zeitgeist of popular culture with hit shows such as Outlander and Fleabag.

Paterson is about to grace our screens in the four-part BBC Scotland drama, Guilt, which continues this week. The darkly comic, helter-skelter tale – written by Bob Servant creator Neil Forsyth – stars Mark Bonnar and Jamie Sives as brothers grappling with the aftermath of a dastardly deed. Here he talks about life, work and the fascinating story behind his remarkable career.

On his role in Guilt

I’m a bit of a bad boy and lean very heavily on our two heroes. They go down a rabbit hole of deceit and dig themselves further in as it goes on. They meet some dodgy and nasty people – and I’m one of them. I don’t think the character I play – Roy – has any redeeming features.

It is not a huge role by any means, but he does have significant influence on the boys. They try to get one over on him and I don’t think that quite works in the way they hoped. I’m a gangland boss who has risen through the ranks and that’s about all you need to know about Roy.

Predominantly my scenes were with Mark [Bonnar], who I have worked with a couple of times before. I played his dad in the ITV drama Unforgotten. Then we did a spoof about the disappearance of Agatha Christie for Sky’s Urban Myths. We have crossed paths over the years.

Playing Fleabag’s dad in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s hit TV show

People call me “Flea Dad”. Being part of Fleabag has been very nice because it is a terrific piece of work by Phoebe.

I came into it after they had done the pilot for the first episode, so I knew what the quality was like and what Phoebe had on screen.

It might have looked very different if it was simply a bald script – you could perhaps have thought it was a bit risque and near-the-bone – but seeing the pilot, I knew that it was well handled. So, I signed up.

Roles which left a lasting impression

I’ve always had a very soft spot for The Crow Road. Not only was it a great book by Iain Banks but, as he said himself on the cover of the DVD, the TV version was “annoyingly better” than the original.

It was a great pleasure to make because the landscape – we filmed it partly in Glasgow and partly in Argyll – was so connected to the story. Then there was this bunch of us as a family: Paul Young, Peter Capaldi, Alex Norton and Stella Gonet.

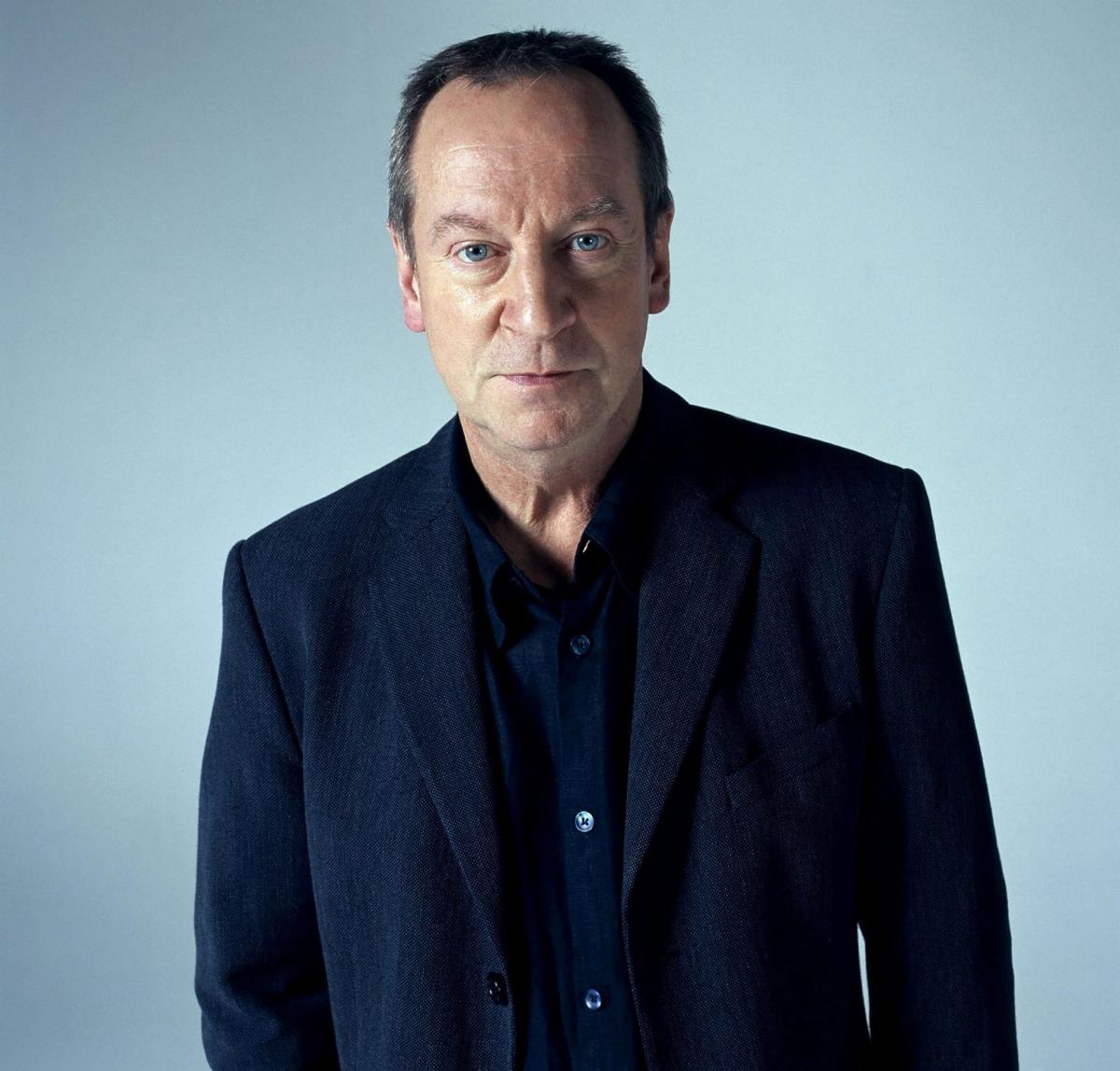

Cutting his teeth in theatre

My theatre days in the 1970s with 7:84 and The Cheviot were life-changing. It changed all of us who were part of it. Not just as actors but because of the impact it had on Scottish politics, Scottish life and Scottish theatrical life.

Alex Norton, John Bett and I had worked together for years from our days at the Citizens Theatre. In the 1970s, we must

have done hundreds of performances together and that left an indelible mark – both laughter and tears. Looking back on it now – almost 50 years later – it feels like another life.

I did Guys and Dolls at the National during that first revival in 1982 when it was thought that it might not be a big success. In fact, there was a real feeling that the critics could well shoot it down and the National could practically collapse under the weight of the disapproval. There was an idea at the time: “Why are they doing a big American musical on the National Theatre stage in London?”

But, in fact, it was the opposite. The friendships I formed have remained with me all my life, people like Jim Carter and Imelda Staunton. The idea of doing a show at the National for 211 performances was unheard of. To some extent, it saved the emotional happiness of the National at quite a difficult time. That stays in the mind.

The secret of career longevity

I did a teaching course at drama college fully intending to teach. I wasn’t planning to be an actor. It just happened that the history and geography of the time, in the late 1960s, there was a lot of emphasis on creating your own material.

It was a bit like the music scene where groups were forming, writing their own stuff and exploring in different directions. Theatre was like that then. I was able – with a bit of luck and timing – to jump on to that train as it was racing along.

If it had been 10 years earlier in the 1950s, I probably wouldn’t have either been caught up in it or been as successful. Another 10 years later, you needed to be perhaps more ambitious than I was.

A love of architecture

I spent three years as a quantity surveyor’s apprentice before going to drama college. I love architecture but if you were keen on the preservation of buildings, the 1960s was not the time to do it. There was an awful lot of disappointment.

Every day you went out there was another part of Glasgow hitting the dust. To be enthusiastic about preservation, you were definitely going against the grain. It wasn’t a great time to be keen on reassessing and reusing buildings.

And the new ones that were going up – the ones certainly I was attached to – were pretty appalling. But I liked the life of being out on building sites and being stuck in the middle of West Lothian on a wet day in February. Fauldhouse, Broxburn, I did them all.

We also did major projects like Falkirk Municipal Buildings. I didn’t do as much in Glasgow even though our offices were based there. My job took me to the glamour spots.

I recently read a newspaper article about plans in the 1970s for Covent Garden in London to be demolished to make way for a vast estate. It talked about how other cities did the same. Thankfully in Glasgow the brakes were put on just about in time – at least in terms of the city centre.

Think of the Bruce Report [a proposal in 1945 to demolish and rebuild Glasgow’s Victorian centre], well, virtually every city in Britain had one of these. I went to see that at the Mitchell Library in the 1960s. I had to go into the Glasgow Room, and when they brought it out, went: “My God …”

Passions away from work

I love walking in cities. My wife Hildegard gets a bit fed up because she will say, “let’s go for a walk over the heath” or “let’s go up this hill” and I’ll say, “But I really like walking in the city”. I like the things that happen in town. I don’t have huge numbers of hobbies. I can’t say I spend my entire time sailing. I wish I had.

On forks in the road

I nearly joined the Navy because I really did like boats. I almost got caught up in that life but it is kind of lucky I didn’t because I realise that if I had become an officer in the Royal Navy – I filled out all the forms to apply – I would have been reaching my heyday about the time of the Falklands War. I would have been there, rather than in Guys and Dolls.

The thing about acting is that you can go on indefinitely provided all the faculties are still working. There is nobody saying: “Well, that’s it, you have to stop now.” In many other jobs, you aren’t going to be physically capable of some things, but you can get away with an awful lot of kid-on in acting.

The evolution of the acting world

In terms of reflecting society on television or film, it is a great process we are going through. With Fleabag, you would get a little bit of people saying: “Oh, it’s just for posh people”. I play the dad in this and I have never at any stage of my life been considered posh.

So, I find it quite an interesting process that is going on at the moment where many people are being able to move into roles that would have been closed to them a few years ago, certainly decades ago. I have been one who has benefited in a lighter way.

I was lucky too in that I came along at a time where you could step into Chekhov and Ibsen and not have to lose a Scottish accent. It wasn’t considered essential that, to pretend to be a Russian in early 20th century Russia, you had to sound as if you came from the Home Counties. People like Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay fought for and made that happen in the 1950s and 60s. That gave great opportunities to people like me.

Luck, chance and opportunity

I have a feeling that if things had been really tough for me, I would probably have crumpled into a heap and disappeared. I haven’t had any big adversity as such, although I did manage to avoid sounding like I came from Roehampton and allowed to stay sounding like I came from Dennistoun.

If I hadn’t taken a very big decision sometime in 1966 to shift out of what could have been a very comfortable life as a surveyor, if I hadn’t grasped that, I could have just drifted on. I would be a retired quantity surveyor today. But that is not an adversity.

Luck is so important. If I had been coming out of drama college in 1959 or 1960, I would probably have drifted into a terrible old rep and not have developed in the way I did. The time was just right. Scotland went through a dramatic renaissance in the theatre during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Those of us who were running around at that time managed to jump on it.

It was meeting great people like John McGrath, who founded 7:84. My old pal Kenny Ireland, we grew up together from our teenage days and I followed in his wake. Without that, I might have fallen by the wayside. You make your life on the support, encouragement and help of others.

One of the things I’m most proud of is that we – my wife [theatre designer Hildegard Bechtler] and I – haven’t wasted any of the advantages we have been given. We didn’t fritter away opportunities. We took them, ran with it and I am grateful for that.

What keeps me awake at night

My prostate. That gets me up at night: going to the bathroom.

I feel like everyone does with the antagonism of our times and the polarisation of the tribes that we seem to be getting into. I don’t do any social media. I have quite a strong dislike for that.

I know the plumbing will go into the cesspool sometime soon, but it is taking its toll on us as a society. That is something that keeps me awake. I get depressed about that.

Do you join it? But then you think, no, you will only add to the cacophony. We will get through it and move on to another phase of understanding.

Guilt is on BBC2, Wednesdays, 9pm with new episodes on BBC Scotland, Thursdays, at 10pm

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here