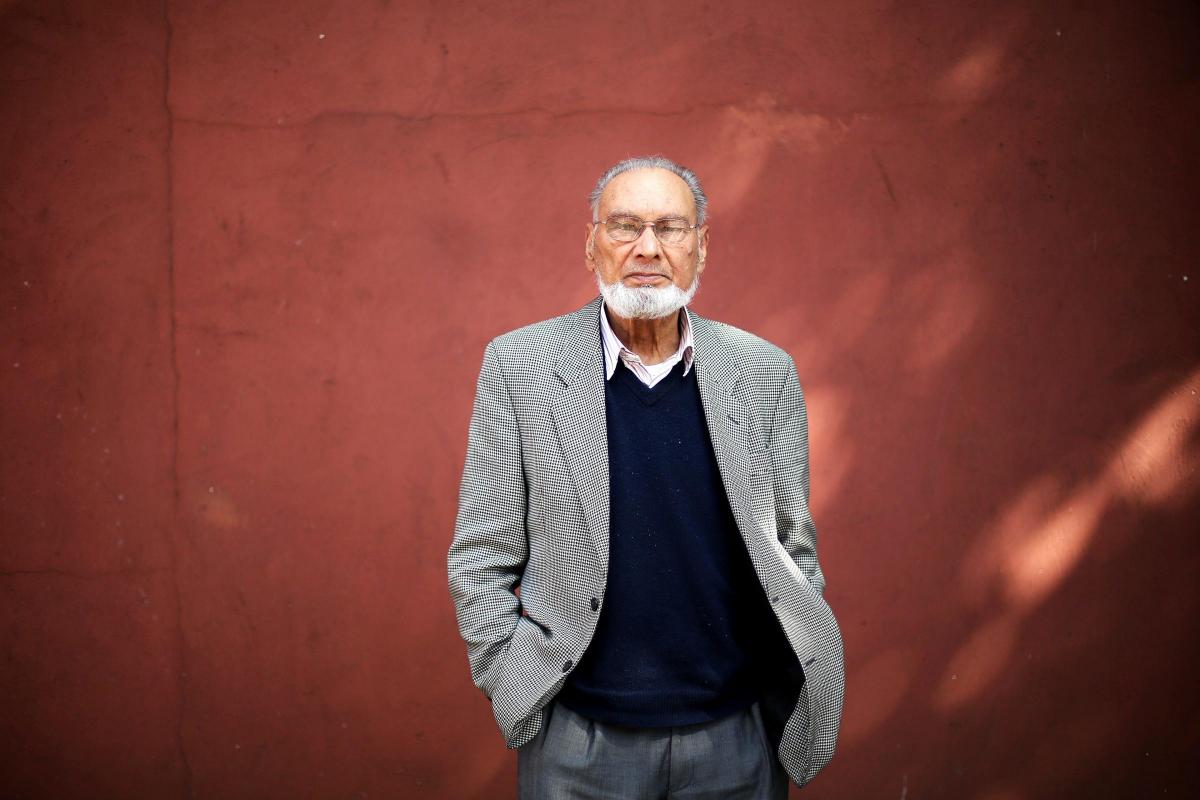

In this edited extract from her book Partition Voices: Untold British Stories, Kavita Puri tells the story of Bashir Maan‘s arrival in Scotland.

Bashir Maan began life in Glasgow selling clothes from a heavy suitcase, door to door, in 1953. Just imagine that. A man who attended Punjab University, whose English was not bad, but no match for the Glaswegian accent, stifling his ambitions and accepting no doubt countless humiliations.

How many doors must have closed in his face? As a young boy he used to laugh with his friends at the Pathans (Pashtuns) from Afghanistan who would come as labourers to the Punjab. Now the same was happening to him. Local kids would follow and pester this exotic figure in the streets and alleys as he tried to sell his wares. "There is a darkie, Johnnie the darkie, hello Mister Darkie, here comes a darkie, darkie, blarkie." But he is not one to dwell on adversities. People were kind, too, especially in the outlying areas of Glasgow – sorry Johnnie they would say, if they didn’t want to buy anything. In those days every Indian or Pakistani was called Johnnie.

Today on his study wall at home hangs a letter from the Queen. It is addressed to Bashir, almost 50 years after he arrived in Scotland. It awards the man who was born in a Punjabi village in British India and came to Scotland after independence, who first worked as a peddlar, the honour of Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his work in public life in Glasgow.

Bashir went on to become the first Muslim city councillor, a district court judge and was heavily involved in race relations and Scottish politics. He had been active in politics since he was a young man, when he was a subject, rather than Commander, of the British Empire. In fact, he had fought against the principle of empire, demanding independence and even a homeland for India’s Muslims. Yet it was the empire that brought him here to Scotland.

Bashir was born in the province of Punjab, in the west of British India, into a village his forefathers had lived in for generations. Like many villages in the Punjab it was mixed; there was a Hindu temple, a gurdwara and a number of mosques nearby. His family were landowners, owning the surrounding wheat and rice fields, and lived comfortably off the rent. It was a peaceful, privileged life.

From 1943 Bashir studied at the nearby city of Gujranwala at a branch of Punjab University. It was the time of Quit India – and he was involved in the Congress Party. "I liked Gandhi." But early on at university a friend introduced him to the Muslim League. Once he understood its aims – a country where Muslims could live according to their own faith and culture, and not subjugated by a Hindu majority – he was convinced and joined up. "I did feel it would be a very good idea," he says. "A Muslim country where we could live according to our religion."

When partition did arrive in August 1947, Bashir was in his village. There was a procession through the streets celebrating the independence of Pakistan. It was triumphant, he reminisces. Gujranwala and the surrounding villages became part of Pakistan. Bashir assumed life would carry on as before. "But then it started to happen."

One day a group of Hindus and Sikhs were migrating to a transit camp where they thought they would be safe. On the way there, they were attacked by a mob of Muslims. Caught up in the attack was a very good Sikh friend of Bashir’s, who was killed. "That was a tragedy. That affected me very much. It was a horrible moment."

Eventually, the movement of their Hindu and Sikh neighbours started. Bashir watched them move out peacefully. "We were sad, they were sad that they were leaving, we were embracing each other, crying."

As the Hindus and Sikhs fled with whatever few bundles they could take with them, most of the houses were left as they were lived in. At night the looters would come and Bashir says he and some friends tried to stop them. They managed to save some contents: utensils, beds, sheets, bed covers. A nearby Sikh temple was made into a store room, and the fragments of the life of the Sikh and Hindu families were put there. Bashir realised that when families migrating from India arrived they would at least have something to start up a new home. As the exhausted, traumatised Muslim refugees from India eventually trickled in, Bashir handed these all out. People who could not share the same land would be sharing something even more intimate: the bed and bedsheets of the other.

Bashir’s first job was in Lahore, where he was in charge of a coal dump. He then took a job as a government clerk. But he was beginning to feel disillusioned with his new country and its politicians. He also wanted an adventure. His younger brother was serving with the Pakistan Navy and had been chosen for training in Rosyth in Scotland. On a trip to Glasgow his brother had been surprised to meet a Pakistani in the street. They kept in touch, and on his return to Pakistan, he told Bashir about the man he had bumped into, a Mr Mohamed. Bashir then decided he wanted to go to Britain and carried on the correspondence with Mr Mohamed. Bashir was warned that life in Scotland was hard, but Bashir was undeterred. "I know what hard work is," he says.

In 1953 Bashir arrived in Glasgow, only intending to stay a few years. He was shocked by what he saw in the country of his former rulers. "It was ingrained in my mind that it was the land of milk and honey. Then I came here and saw the dirt in the street and little boys playing in their bare feet. I thought 'Oh my God!'" On Hospital Street he saw a briquette-seller covered black with soot – and the people buying the coal looked so sad. "I was very surprised these were the kind of people who were ruling over us. Over there they were dressed up and clean, and then over here this was the situation."

He lived in a house with other peddlars who sold knick-knacks door to door. When he started hawking, his English was rusty, but it soon improved as he was speaking to Scottish people all day. He continued his studies and gradually became vocal in the press in talking about community issues. In 1969 he was persuaded to stand as a city councillor for the Labour Party. To his astonishment he beat four native Scottish candidates and became the first Muslim in the country in that position. It was, he laughs, almost like a "miracle" that he won. Bashir brought his wife over from Pakistan in 1961. Though he only intended to stay a few years, he has now spent the majority of his life in Scotland, though you could not tell from his accent. There is not even a slight Glaswegian twinge. He says Scotland has given him more opportunities than Pakistan could. He describes himself as Scottish Pakistani. Home is Glasgow. Even though he returns to his village in Pakistan every year, after a few weeks away he yearns to come back. He misses his friends, interests, even the Glaswegian weather.

At the age of 91 he is still planning to return to his village. He enjoys the simple life there. "I go to the places that I liked to play in my childhood." The man who campaigned with the Muslim League for an independent Pakistan now says that with the benefit of hindsight it would have been better if India had stayed together, and given guarantees to its Muslim citizens. The houses of Hindus and Sikhs, left 70 years ago, still stand in his village – solitary reminders of a time when this land was lived on not only by Muslims. "We were all disappointed by what happened, because none expected it would come to this."

This is an edited extract from Partition Voices: Untold British Stories by Kavita Puri, published by Bloomsbury, out now, priced £20.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel