If you are a doctor, researcher or scientist who just happens to define the symptoms of a disease or its cause, then the greatest honour you can be given by your peers is to have that disease named after you.

Such well-known diseases include Parkinson’s, Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and Alzheimer’s, while Bell’s Palsy is named after a Scot, Sir Charles Bell, the Edinburgh-born surgeon and painter who has several medical attributions to his name.

The subject of today’s column is another Scot, Sir David Bruce, whose eponymous disease is brucellosis, once a hugely feared infection that, in many cases, led to death.

As was shown in last week’s column, Bruce is one of the men named on the frieze around the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and he deserves his place there because even though profited from other people’s work in discovering the cause of brucellosis, he personally discovered its cause and the cause of one of Africa’s worst diseases, sleeping sickness or trypanosomiasis, and how it was transmitted by the tsetse fly.

Bruce was not actually born in Scotland. His father, also David, was in Australia helping to build crushing machinery for a goldfield having emigrated with his wife Jane, nee Russell Hamilton, at the start of the 1850s. Bruce was born in Melbourne on May 29, 1855, and was his parents’ only child.

They returned to Scotland when he was just five, and the boy was educated at Stirling High School. As a teenager he went south to Manchester and took up an apprenticeship with a warehousing firm. The real reason he may have gone to England was to take up a career as an athlete, as he had grown into a strapping muscular lad. However, any such ambition, and indeed his time in industry, ended when he caught pneumonia and had to return to Scotland.

During his recuperation, Bruce thought hard about what he wanted to do with his life, a career in industry no longer being attractive to him. As a child, Bruce had been something of an ornithologist and being keen on working with birds and animals, from 1876 Bruce studied zoology at Edinburgh University. After a year of study, however, his true talents were recognised and he was persuaded to study medicine at the University’s famed Edinburgh Medical School from where he graduated in 1881.

His first position was as a general practitioner in Reigate in Surrey, and though he did not last long there, he did meet and marry his wife Mary, nee Steele. She would become hugely important in his career, and as we shall see, they were very much a couple who were devoted to each other for the rest of their lives.

At University, Bruce had a keen interest in pathology and the developing field of microbiology, and truth to tell, he was not really cut out for general practice, being a no-nonsense often brusque character. Having married Mary he promptly enrolled at the Army Medical School which was then sited in Hampshire at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley. The Hospital itself had been built at the suggestion of Queen Victoria after the debacles of the Crimean War.

Bruce very quickly qualified for the Army Medical Services into which he was commissioned as a surgeon captain. In 1884 he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and was soon stationed at Valletta in Malta. Mary joined him there, and soon Bruce was working on a mysterious illness which sometimes resembled typhoid fever and at other times malaria, and which was known as Malta, Mediterranean or Undulant Fever.

Beginning a methodical investigation of a disease that affected large parts of the local population and the British garrison, Bruce travelled around Malta and its sister islands Gozo and Comino and was shocked by the pervasiveness of the fever which he calculated was the cause of 120,000 ‘disease days’ annually and led to death in two per cent of cases.

He was held back by the lack of research equipment at the hospital, but in 1886 was able to purchase a microscope. He had been a follower of the work of Robert Koch, the German who is often credited as being one of the fathers of the science of microbiology, and applied Koch’s ideas to the study of Malta Fever.

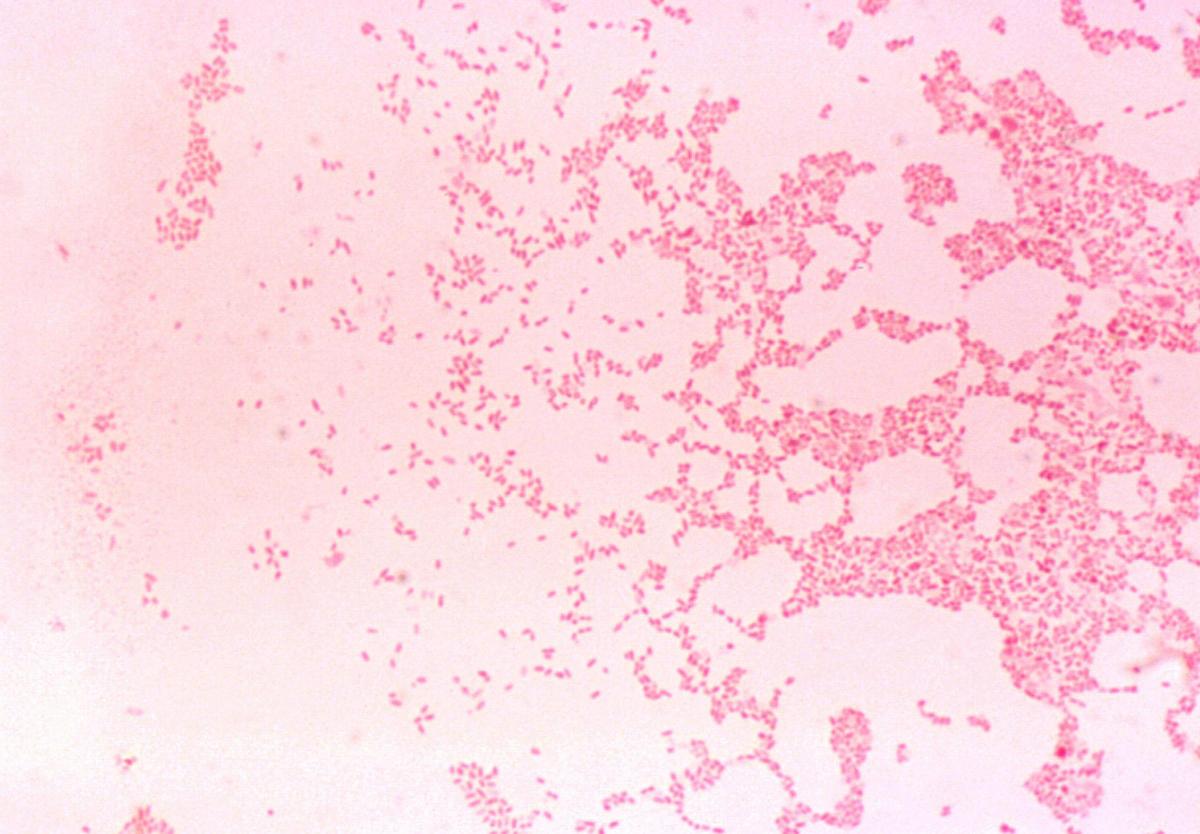

Late in 1886, Bruce found what he described as “enormous numbers of single micrococci” in the spleen of a patient who died of Malta Fever. Bruce was able to grow a culture of the micrococci and in 1887 he reported on his findings and named the organism Micrococcus Melitensis. Bruce had now identified the case of Malta Fever, but he did not know how it was transmitted and could not name the source. A cure therefore seemed very far off.

Bruce was recalled from Malta in 1889, and on his way home he visited Koch’s laboratory in Germany. Meanwhile his wife Mary went about learning the latest techniques in microscopy, as well as staining and media making – for it would be she who would devise the many superb drawings that distinguished Bruce’s work.

Having been promoted to Assistant Professor of Pathology at the Army Medical School at Netley, Bruce now introduced the bacteriological experimentation methods of Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and above all Robert Koch.

Always anxious to travel and have the life of a soldier, in 1894 Bruce was posted to Natal, whose governor asked him to investigate an outbreak of a disease called nagana that was affecting cattle and horses in northern Zululand. It was the bovine and equine equivalent of sleeping sickness in humans which no less a personage than Dr David Livingstone had called tsetse fly disease as it always seemed to occur where concentrations of the insect could be found. It was very debilitating disease and often fatal in all species and Bruce tasked himself with finding the cause, soon suspecting that nagana and Livingstone’s tsetse fly disease were one and the same thing.

Bruce’s long-suffering wife Mary accompanied him on a five week trek by ox wagon to a place called Ubombo, in what is now northern KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, where they worked in a mud hut for two months. A series of observations by microscope led Bruce to conclude that the cause of the disease was a parasite known as a trypanosome, and with experiments on horses and dogs he proved that it was transmitted by the bite of a Tsetse fly, though its human equivalent had still not been traced. His discovery was lauded back home in the UK, and he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.

There then came a remarkable period in Bruce’s life when he was finally able to go on active service due to the outbreak of the Second Boer War in October, 1899. He and his wife were posted to Ladysmith and were caught up in the siege of that town which lasted for 118 days.

Due perhaps to Bruce’s newfound fame, he was able to persuade the British and Boer commanders to allow him to establish a neutral field hospital three miles outside Ladysmith where Mary became the head of the nursing corps. They treated 10,000 patients during the Siege, service for which he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and she was recognised with the highest honour of the Red Cross.

After the war David and Mary Bruce returned to Britain and met with great acclaim. Bruce was now determined to attend to unfinished business. In 1903 he joined the Royal Society‘s expedition to Uganda to investigate sleeping sickness in humans, as well as working with an army commission investigating dysentery in military camps. It was the second sleeping sickness commission sent out by the Royal society, the first having been sent out in 1902 a year after a devastating outbreak killed an estimated 250,000 people In Uganda.

A member of that first commission from 1902, Dr Aldo Castellani, suggested that trypanosomes in spinal fluid might be the cause of the disease. Bruce was sceptical at first but he could not deny the evidence which he began to amass and he eventually proved that the parasite was delivered to its host by the tsetse fly. It would be many years before drugs were developed to combat sleeping sickness but preventative measures encouraged by Bruce’s discovery of the link with the tsetse fly saved countless lives.

He had yet more unfinished business, this time back in Malta. Bruce began to call for more investigation into the cause of the disease that he had first begun looking into almost 20 years earlier.

The government set up the Mediterranean Fever Commission and put Bruce in charge of it. Thanks to Bruce it was known that the micrococcus melitensis was responsible for the illness, but still no one knew how it was spread. One expert had written a book in 1897 specifically stating that milk could not be a causal agent but as the commission began its work, suspicions soon alighted on the milk of Maltese goats, the animal which was the most prevalent domestic creature across the archipelago.

Commission member Dr Themistocles Zammit carried out experiments in 1905 which proved that the Maltese goat was affectively a reservoir of the bacteria which caused Malta Fever. Bruce doubted his colleague’s work at first, but eventually accepted the verdict and having done so, he wasted no time in reporting his recommendations to the Government which instructed the army to take immediate

As the Royal Society records: “In 1906 the use of goat’s milk by the British Army was banned completely; between 1900 and 1906 there had been 3,631 cases of Mediterranean fever in the British Army but by 1907 there were only 21.”

Sadly, local people stuck to their milk. As The Royal Society notes: “However, this ban did not prevent cases in the Maltese population, where the disease continued to be widespread, and it was not until 2005 that Malta was finally Mediterranean fever-free.”

The disease is still found across the world, often due to failures in pasteurisation techniques, and though he did not discover the infecting agent and did not devise a complete cure, Bruce was honoured by the medical community adopting the name brucellosis for the disease.

There have been several reports over the years that Bruce tried to downplay the efforts of his juniors in his discoveries about sleeping sickness and brucellosis. There is some evidence to that effect, for Bruce was known as an egotistical person – his blunt speech was famous yet his reputation remains high because of his discoveries.

He was knighted for his work in 1908 and was showered with many other awards. He should have retired from army service in 1911, but his many supporters campaigned for Bruce to be kept on – so much so that he was promoted to Major General and made commandant of the Royal Army Medical College during World War One.

He eventually did retire in 1919 and was able to spend more time with his beloved Mary who had helped him write more than 30 publications and was always by his side until she died on November 23, 1931. Sir David Bruce, who had been suffering from cancer, collapsed and died at her memorial service just four days later.

His epitaph is from a speech given in 1924: “We are all children of one Father. The advance of knowledge in the causation and prevention of disease is not for the benefit of any one country, but for all.”

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here