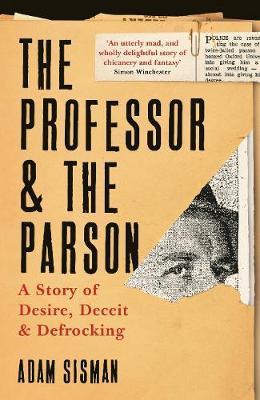

The Professor & The Parson: A Story of Desire, Deceit & Defrocking

Adam Sisman

Profile Books, £12.99

THE famous – and in some regards infamous – historian Hugh Trevor-Roper first encountered Robert Peters in 1958. At that time, Trevor-Roper was near the pinnacle of his profession. His still wonderfully readable and enthralling book, The Last Days of Hitler, published in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, was a critical and popular success. Now, aged 44, he was Regius Professor – how academics love their titles – of Modern History at Oxford. While there he received a letter from a woman who said she had as her lodgers a married couple called Peters. The pair, she believed, were victims of “vindictive persecution from outside the university”.

Trevor-Roper’s curiosity was piqued and he arranged see Robert Peters at his office. He told the historian that he was 34 – though he looked older – and that he was an ordained priest, which, like much of what he said over the forthcoming decades, may or, more likely, may not, have been true. His persecutor, he said, was none other than the Bishop of Oxford, who was not allowing him to officiate in his or any other diocese. This, Peters protested, was humiliating, insulting and unjustified, and he begged Trevor-Roper to mediate, which – mischievous fellow that he was – he offered to do.

It was the beginning of a tortuous, intriguing and barely believable story, which sheds a fierce but comic spotlight on the ineptitude, gullibility and naivety of countless senior prelates and academics who were taken in by a consummate and unrepentant charlatan.

Adam Sisman stumbled on Peters while researching his biography of Trevor-Roper. As he relates in the introduction to The Professor & The Parson, he found among his subject’s papers a thick folder with Peters’ name on it. It contained a dossier that the historian had added to for more than two decades. A novelist would have difficulty in inventing the narrative that unfolded as Sisman read. As he concedes at the outset, “Studying Peters is like tracking a particle in a cloud chamber: usually one cannot see the man himself, but only the path left behind.”

Thus, for the 200 or so pages that follow, the reader feels like a detective in pursuit of an elusive quarry. Just as you think you are about to feel Peters’ collar, and get a real sense of who he is and what motivates him, he slips away, reappearing in the most unlikely places – from Aberdeen to South Africa with innumerable stops in between – and in the most bizarre of guises. By Sisman’s count, he married at least seven times, often bigamously, and may have been married an eighth. He had at least one child but of him we learn little. Who knows, there may have been others.

Peters was persistent in his determination to find jobs both in the church and academia. When none was forthcoming he founded colleges, whose courses were validated by mainstream universities, and appointed himself principal. His qualifications were impressive though virtually all were invented. Often this did not matter. There were many institutions prepared to hire him on the basis of a perfunctory interview or an ersatz resumé despite the fact that he often appeared in tabloids, rumbled as a bigamist and fraudster. He spent time in jail and was deported three times from the United States, to cite but one country where he was not welcome. He thought nothing wrong with plagiarism and, where women – especially young women – were concerned, he was a creep.

On one wonderful occasion, Trevor-Roper turned on the television to find Peters appearing as a contestant on Mastermind. His chosen subject was the life of William Temple, former Archbishop of Canterbury. According to Sisman, he answered seven questions right and got nine wrong. This prompted the News of the World to send a reporter to track him down. “Are you the same Rev. Peters, alias Parkins, who was unfrocked in 1953 by the Church of England after a bigamy scandal?” he was asked. Peters burbled but when he interrupted another question, the reporter replied: “I’ve started, so I’ll finish. Do you have a record of lying to obtain teaching jobs?”

The Professor & The Parson is divided into three parts. The first describes the initial encounter between the history man and the trickster. The second is heavily dependent on a document written by the former when he may have been considering turning what he’d found into a book. The third is concerned with what happened after Trevor-Roper threw in the towel and what Sisman himself has discovered about Peters. It all makes for a dizzy and diverting read.

There is, of course, a lively literature concerning those who, dissatisfied with their real lives, create others more to their liking. Trevor-Roper himself wrote a brilliant one, The Hermit of Peking, about Sir Edmund Backhouse, a notable sinologist. Another classic of the genre is AJA Symons’ The Quest for Corvo, whose subject, Frederick Rolfe, who nurtured dreams of becoming Pope, may well have inspired Robert Peters. Yet another worth mentioning is Joseph Mitchell’s Joe Gould’s Secret, the eponymous hero of which managed in the 1940s to convince the gullible hipsters of Greenwich Village that he was writing a nine-million-word book called An Oral History of Our Time when in fact he was a graduate of Harvard who’d fallen on hard times and become a bum.

Why Peters behaved the way he did is unclear and, without testimony from the man himself, unknowable. Status seemed to matter more to him than money. If self-delusion is an illness he had a severe case. But what no one can doubt is his self-belief. He was often down but never entirely out. He died in 2005, aged 87. Equally intriguing is Trevor-Roper and why he never wrote the book that Sisman has. The likeliest explanation is that his erroneous authentication of the Hitler Diaries, which were shamelessly serialised by the Sunday Times, and his subsequent pillorying, made it impossible for him to write about a hoaxer when he himself had been so publicly duped by one. As Sisman says, “The damage to his reputation was permanent and irreparable.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here