IT is axiomatic that when you take a view on a historical matter you should always do so in the context provided by history. That is why I disagreed with the Scottish Government’s decision last year to remove references to Sir John A. Macdonald, the first Prime Minister of Canada, from the Scotland.org website following what the Government called “the legitimate concerns raised by Canadian indigenous communities about his legacy”.

I am glad to say that articles about Macdonald have been restored to the website with a description of the controversies that surround Macdonald to this day, almost 128 years after his death.

That is something that should have been included when the articles were first posted.

For as the recent brouhaha over Green MSP Ross Greer’s spat with Piers Morgan about Winston Churchill demonstrated, it is just plain wrong to alight on one or even several aspects of a great person’s life and say that these aspects define the person entirely. With historical figures you have to take a balanced view of them within the context of the times and culture they lived in because to do otherwise is too simplistic. Revisionism is perfectly justifiable, but only if it’s done in a nuanced fashion.

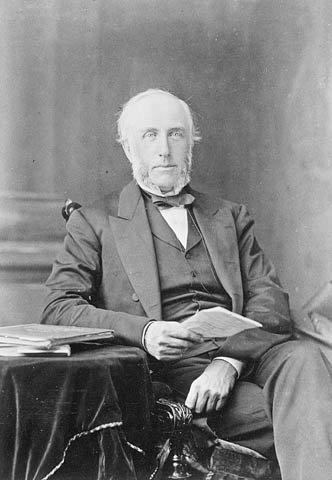

As we shall see, Sir John Alexander Macdonald is rightly feted for his magnificent achievements in the creation of Canada, but just as last week’s Back In The Day profiled Scottish-Canadian hero, Andrew Mackenzie, as an explorer keen to expand the British Empire, so we will acknowledge Macdonald’s motivations and examine his conduct. For like Mackenzie, Macdonald, too, was a creature of Empire and a British subject through and through.

Born in Ramshorn Parish in Glasgow city centre on January 11, 1815 – there’s a blue plaque on Ramshorn Kirk in Ingram Street to commemorate him – Macdonald was the son of a perennially unsuccessful businessman named Hugh and his wife Helen, nee Shaw. In a bid to start afresh and probably throw off his debts, Hugh Macdonald took his family to Kingston, now in Ontario but then part of Upper Canada.

Though he was only five when they emigrated, Macdonald remained proud of his Scottish roots all his life.

Hugh Macdonald tried running shops and taverns but with no success. The family also suffered tragedy when an employee beat John’s younger brother James to death as seven-year-old John watched.

The family had enough money to get John Macdonald an education of sorts but could not afford to send him to university. British North America, as the land was then known, had no law schools so he became an apprentice lawyer and was called to the Bar in 1836 at the age of 21. He soon became prominent in legal circles as a renowned criminal defence lawyer.

He was also growing wealthy and after his father died in 1841 he was able to take an extended holiday in Britain where he met, and later married, his cousin Isabella Clark.

Having been voted in as an alderman, after the UK Parliament merged Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada in 1841, Macdonald stood for election to the new legislature in Canada West – as Upper Canada became, Lower Canada becoming Canada East - and was rapidly successful, winning the Kingston seat as a Conservative in 1844 and becoming a Queen’s Counsel two years later followed by a spell as a Government minister until the Conservatives lost the 1848 election. Macdonald kept his seat but family tragedy struck again with the loss of his son John Jnr in that same year.

It was noted that Macdonald took to drink to ease his sorrow but continued to drink heavily even after his son Hugh John was born in 1850. Indeed, he would often drink large quantities and suffer “lost weekends”.

Once while debating with his arch-enemy George Brown he was heckled for being three sheets to the wind. Macdonald replied: “Yes, but the people would prefer John A. drunk to George Brown sober.”

THOUGH kind and personable in private, Macdonald was a ruthless politician and quite cynical. He once wrote: “There were, unfortunately, no great principles on which parties were divided – politics became a mere struggle for office.”

He became leader of the Canada West Conservatives and in opposition from 1848 to 1854 he promoted the British America League which wanted to unify Canada and strengthen ties to Great Britain – though even he would often refer simply to England.

The difficulties of keeping Canada West and Canada East going were mounting, and so did demands for reform. Macdonald rode the wave and formed a coalition with the Liberals of Canada East so that he became Prime Minister of the province of Canada in 1857. That year saw his fellow Scot, the newspaper owner George Brown, a native of Edinburgh, enter the Province’s Parliament as a Reform candidate.

Again Macdonald suffered tragedy when his wife Isabella died, leaving him a widower with a boy of seven. Young Hugh would largely be raised by his aunt, and indeed both his sisters and mother played a large part in John Macdonald’s life. He married again, to Agnes Bernard, and their only child was Margaret Mary Theodora who suffered from hydrocephalus but largely overcame her disability to be an accomplished typist of her father’s speeches.

Brown and Macdonald did not like each other, but buried the hatchet long enough to form a coalition that called for Canada to become a Confederation – in effect an independent country under the Crown.

This was to be Macdonald’s greatest project. In a long speech proposing the new plan in October, 1864, he laid out the possible constitution.

He wanted a strong central government and argued cogently for saying it would “strengthen the Central Parliament, and make the Confederation one people and one government, instead of five peoples and five governments, with merely a point of authority connecting us to a limited and insufficient extent.”

He wanted “all the advantages of a legislative union under one administration, with, at the same time the guarantees for local institutions and for local laws, which are insisted upon by so many.”

Though not a noted orator, Macdonald had a turn of phrase that certainly looked good on paper. He wrote at that time: “There may be obstructions, local differences may intervene, but it matters not — the wheel is now revolving, and we are only the fly on the wheel, we cannot delay it. The union of the colonies of British America under one sovereign is a fixed fact.”

He also coined this: “Anybody may support me when I am right. What I want is a man that will support me when I am wrong.”

In that 1864 speech, Macdonald sent out a powerful plea for unity, declaring Canadians should form and be one people. He had answered the big question, whether Canada would be a country at all. His answer in short was this —we will be one people, we will be united, and we will be free.

To digress: in the course of that long opening speech, Macdonald explained his thoughts on the Union that created the British Empire: “The relations between England and Scotland are very similar to that which obtains between the Canadas. The union between them, in matters of legislation, is of a federal character, because the Act of Union between the two countries provides that the Scottish law cannot be altered, except for the manifest advantage of the people of Scotland.

“This stipulation has been held to be so obligatory on the Legislature of Great Britain, that no measure affecting the law of Scotland is passed unless it receives the sanction of a majority of the Scottish members in Parliament. No matter how important it may be for the interests of the empire as a whole to alter the laws of Scotland—no matter how much it may interfere with the symmetry of the general law of the United Kingdom, that law is not altered, except with the consent of the Scottish people, as expressed by their representatives in Parliament.

“Thus, we have, in Great Britain, to a limited extent, an example of the working and effects of a Federal Union, as we might expect to witness them in our own Confederation.”

Would that Macdonald were alive today to point out how that “Precious Union” has been traduced by successive Westminster Governments who say that “the UK Parliament is sovereign, the Scottish Parliament is not.” (c. Lord Keen).

The Parliament in London voted to back the new Confederation and the Dominion of Canada was approved in the British North America Act given Royal Assent on March 29, 1867. There could be only one Prime Minister of the new country, Macdonald being given a knighthood by Queen Victoria to mark his new post, and he would serve six years in that role.

During that term Macdonald proposed the establishment of one of the world’s most famous police forces, the North West Mounted Police, later the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or Mounties.

He stated: “They are to be purely a civil, not a military body, with as little gold lace, fuss, and fine feathers as possible, not a crack cavalry regiment, but an efficient police force for the rough and ready - particularly ready - enforcement of law and justice.”

For that institution alone Macdonald would be remembered, but he did so much more and despite being implicated in a huge scandal concerning the railways opening up western Canada, he was re-elected as Prime Minister in 1878 and kept that office until his death in 1891. During his time in charge the Canadian economy was transformed and other territories such as British Columbia joined Canada as we know it – that’s why he is often called the father of the nation.

Sadly, not all of his works were good and proper as we would see it today. As it states on Scotland.org: “Recently, controversy has surrounded some of Macdonald’s government’s policies in relation to the indigenous people of Canada during his time both as Prime Minister and Minister of Indian Affairs.

“This includes the development of the Residential School system, which forcibly removed many thousands of indigenous children from their families to ‘westernise’ them. As well as this, Macdonald’s government also withheld food rations from some western indigenous communities, in a bid to pressure them to move into reservations.”

That is a summary of what happened. Perhaps some 150,000 children were forcibly removed to boarding schools to be taught English and to forget their native culture. The people of the First Nations remain angry about it. Yet, for him, that was a logical process because he was, first and foremost, a British imperialist.

In his last electoral address in Ottawa in 1891 he said: “A British subject I was born; a British subject I will die.

“With my utmost effort, with my latest breath, will I oppose the ‘veiled treason’ which attempts by sordid means and mercenary proffers to lure our people from their allegiance.”

For all his faults, and they were legion, Sir John Alexander Macdonald achieved great things for a country that is close to the heart of many Scots. Our friends, Canada.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here