THEY were out to kill him, but he had already escaped from Mosul. Tip-toeing through the broken glass strewn across the floor, Loay Francis Namrud, continues telling his story of how the jihadists of Islamic State wanted him dead.

His two colleagues at the local Mosul newspaper al-Haqiqa, where he was an editor, were not so lucky he said.

“Hashem Fares a photographer and Rasha Altay another editor were executed, shot,” he tells me, stopping in front of a decapitated statue of Christ that lies on his living room floor.

“Daesh knew my family were Christians,” he continues after a brief pause, adopting the commonly used Arabic acronym here for the Islamic State (IS) group.

“This was the message they left us,” he says, looking down at the plasterwork figurine that has had its head, hands and feet hacked off. “Daesh do this to real people too, of course,” he adds as an after thought, shaking his head.

He is a small, alert man, chain smoking as he talks. We are standing in the fire blackened and ransacked interior of his home in the town of Telskuf that lies just north of Mosul.

In the past week Loay and his family have returned to what was once a predominately Christian community, but their house is uninhabitable and for now they are forced to rent another place nearby.

It was early August 2014 when IS fighters first overran Loay’s neighbourhood, but within weeks Kurdish peshmerga forces recaptured it. Last year the jihadists returned but were again forced back.

“It wasn’t safe for us to stay here as we were always on the frontline, so I took my family away and of course had to leave my newspaper job in Mosul,” Loay says with a shrug of resignation.

His house was once grand but today its sits charred, its balconies still lined with sandbags that were IS machine-gun emplacements. Dog excrement litters the floor from the feral packs that roam the area. Everywhere the belongings his family left behind in their rush to escape lie in smashed or torn heaps. Not one item seems to have been left untouched.

In a bedroom lie piles of his children’s clothes, while outside in the backyard a safe in which he kept precious family documents and work files has been prised and blown open.

“Before Daesh left, they put bombs, traps, everywhere, we still must be careful,” he warns.

“When our soldiers retook the area, Daesh retaliated with suicide bombs and their fighters that were living here in our house blew themselves up,” Loay says, his look suggesting he still struggles to comprehend what they did.

In Telskuf and nearby Batnaya, a village that sits even closer to Mosul, the jihadists and those who fought them have left many scars on the physical terrain and the psychological landscape of those who lived here. Across communities in and around Mosul it’s the same story.

Walking through the deserted and devastated streets of Batnaya, where up to 80 per cent of buildings have been destroyed, there is now an eerie silence save for the sound of coalition warplanes in the sky above and the percussive crump as they drop their bombs a few miles away to the west of Mosul.

The soldiers with me, some of whom helped retake Batnaya, keep up a running commentary, pointing out trenches lined with plastic tarpaulins and filled with oil that IS fighters would set alight to create huge clouds of thick black smoke as cover against the planes while the jihadists fought street to street on the ground below.

On Batnaya’s few remaining walls, mortar bombs and rocket-propelled grenades have gouged their tell-tale spatter-mark tattoos into the concrete.

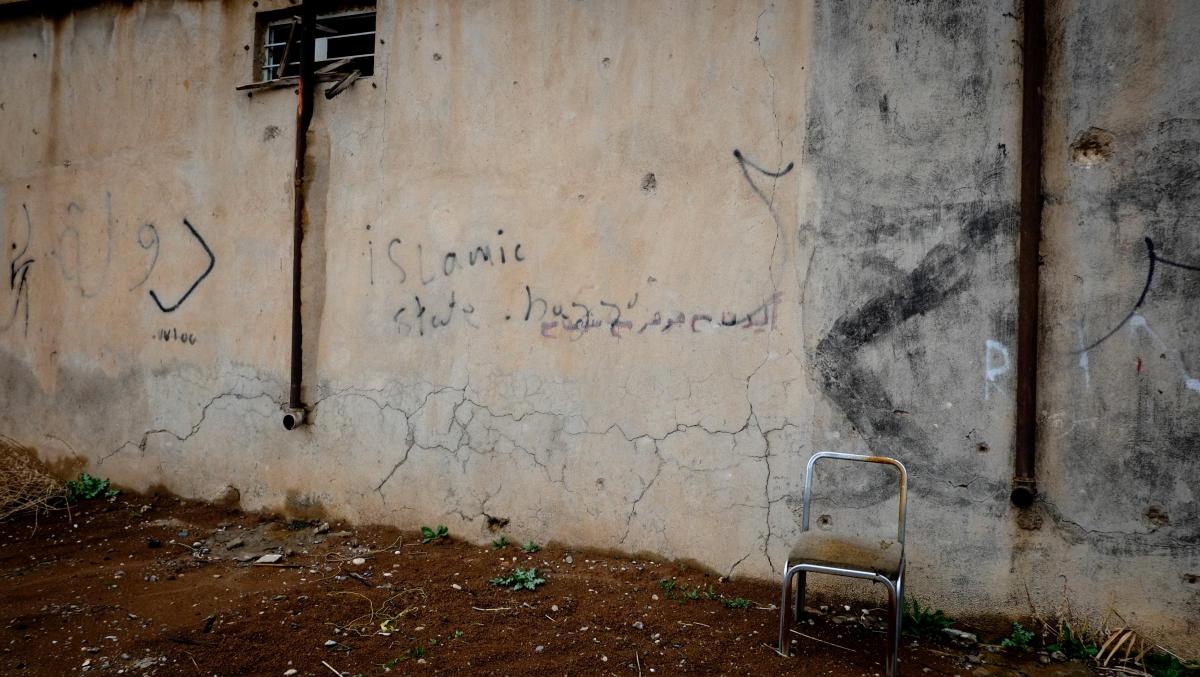

Outside one house the words Islamic State are spookily spray painted in English on a wall against which leans an empty chair. One can only guess what became of whoever sat there. In this warren of rubble, suicide bombers and snipers ruled, just as they do right now in west Mosul, where the worst of the battle against IS continues. As ever innocent civilians find themselves caught in the hellish crossfire.

“There was still fighting nearby, but our street had been liberated a few days earlier by the Iraqi Army, so I thought it safe to go outside the house,” Asud Ali Saeed, tells me.

Seconds after stepping through his front door he found himself crumpled in the street of west Mosul’s al-Maamoun quarter, blood spurting from his stomach into the dirt.

“I didn’t think I would live,” he admits.

That he did survive is largely due to the skill of Dr Mansour Marood, who shortly afterwards operated on Asud Ali.

In the ward of Qayyarah General Hospital, an oil town that sits south of Mosul and that itself was fiercely fought over, Dr Marood talks of that hectic day when Asud Ali was brought in and the seemingly endless days like it that continue as the battle for Mosul intensifies.

“On one occasion we had hundreds of people, not just those suffering gun and blast injuries, but many who had inhaled toxic gas from the sulphur plant that Daesh set on fire near here,” he recalls.

Right now the vast majority of casualties the hospital receives come from west Mosul. Just a few days ago as I stood talking to Talib and Muhammed, two brothers in their 20s, who had been forced to flee that district because of the fighting, someone came up to tell them the unimaginable news that their other two younger brothers had been the victims of a rocket attack in west Mosul.

One had died instantly, the other was fighting for his life at Qayyarah General Hospital. How old was the brother that died? I asked Talib, his dirty and weather-beaten face already tear stained.

Choked with grief and unable to speak, he simply held up the thumbs and fingers of both hands. His brother was 10 years old.

Walking through the multi-storied building of Qayyarah General Hospital, with its dilapidated corridors and wards, I wondered in which part of the building Talib’s little brother had spent his last moments.

I tried to imagine too what it must have been like in the hospital when IS ran it after they occupied Qayyarah. Speaking of that time, Dr Mansour tells of IS medical staff treating their own battlefield wounded but very few, if any, local casualties. The doctors and medics who worked for the jihadists, he says, were clearly professionals, making use as they did of the operating theatres on the hospital’s upper floors.

As Qayyarah was retaken by advancing Iraqi forces and the jihadists were forced to retreat, they took everything they could with them.

“Surgical instruments, equipment, anything they could transport was moved, probably back to Mosul,” Dr Mansour suggests.

As ever the group’s retreating fighters and cadres littered their retreat with booby traps and bombs that they rigged across the hospital.

“What they couldn’t carry they immobilised, and knew precisely what they were doing,” Dr Mansour continues, telling how IS removed a key component from a CT scanner without which it wouldn’t work.

Most of the current casualties from west Mosul that end up in Qayyarah, have come through the nearby town of Hammam Alil. Until the operation to retake Mosul from IS began, this was an insignificant place on the banks of the Tigris River. Last year though it suddenly became infamous after the discovery of 100 beheaded bodies in the town’s College of Agriculture and Forestry, a massacre carried out by IS.

Hammam Alil is also the conduit through which most civilians now escaping west Mosul come. While some end up in camps there, others are moved to locations further east where existing camps are already at maximum capacity.

Chamakor Camp is one of the newest, sitting above a narrow river and ringed by low hills and villages smashed by heavy fighting in the earlier stages of the Mosul assault.

As the bus carrying the new arrivals snaked its way down the dirt road towards the camp, I could just make out the faces peering from the windows.

It drew closer and the faces became clearer – the exhaustion and apprehension of those on board was unmistakable.

Stepping from the bus, their clothes ragged and dirty, many of the men still had the heavy beards IS religious diktats demanded they wore while under the jihadists' rule. Some of the women with exhausted children in tow nervously kept their faces covered.

Each and every family carried the meagre belongings that they had managed to grab before escaping. For most it amounted to no more than a few bags and blankets.

Carried from the bus by one of her grandsons, 90-year-old Khatla Ali Abdallah was tenderly placed on the ground among her bags. This was the final stage of her harrowing and exhausting journey from west Mosul.

Living for the most part in a basement with only her chickens for company, she survived battles the like of which never existed even during the turbulent years of Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship.

“I’m very tired, it has been a long way,” Khatla told the young female aid worker who knelt down to offer the old lady bottled water. Reaching for the bottle Khatla first kissed the girl’s hand, expressing her thanks for the help.

Khatla’s remarkable story had preceded her arrival at Chamakor Camp and has already almost entered the realms of folklore.It is a remarkable tale of fortitude and resourcefulness which at its height involved being carried by her grandsons, under sniper and mortar fire, before making the town of Hammam Alil.

“I was carried like a bride at her wedding,” Khatla told those eager to hear her story. What will happen to you now? I asked, as she sat on top of her bags outside Chamakor Camp last week.

“When the fighting is finished, my grandsons will carry me back again,” she told me matter-of-factly. That she survived the journey out through Mosul’s frontlines was little short of miraculous.

Just a few days earlier, not far from where I encountered Khatla, I spoke with a man called Abdul Wahid Ali, who had made the same dangerous trip that also involved crossing the Tigris.

“We crossed at night in the darkness,” the former nurse from Mosul told me. “My family were in small boats alongside others carrying our neighbours, but Daesh saw us and started shooting and some of our friends fell into the water or were killed by the bullets,” he recalled.

At Chamakor that day, Khatla’s family and dozens of others who had made it out of west Mosul were given their first hot meal in days, and began the process of registration before being allocated a tent that will be their home for the foreseeable future.

In the coming months temperatures on the desert plain on which Chamakor sits will reach the mid-50s Celcius and conditions will become intolerable, not least for the many young children that now inhabit these camps.

Many more youngsters arrived that same day as Khatla, two generations thrown together by the tide of war.

Among them, one little boy stood out. He could not have been more than 10 years old and from the moment he stepped from the bus, it was clear the trauma of the terrifying journey he had undertaken had taken hold of him.

Tears streaming down his cheeks, there was a terror and helplessness in his eyes. His pain was heartbreaking to witness, his vulnerability overwhelming.

In the chaos of arrival and immediate efforts by aid workers to take him under their wing, I never did find out his name. All I could subsequently establish was that he too was from west Mosul and had fled with his family.

Scurrying out of the city under fire, confusion and panic all around, he had become separated from his loved ones.

As I watched him weep uncontrollably, I found it hard to imagine the pain and anxiety he must be going through. One little boy lost amidst war and cast adrift from his parents who now faces a future as uncertain as Iraq itself.

He will not be the last of the innocents here caught up in the cauldron of war.

Mosul is not yet liberated from the brutal tyranny of IS rule. Even when freedom from the jihadists does come, things will be far from peaceful in Iraq.

For the moment, ordinary civilians continue to bear the brunt of this bitter struggle for Iraq’s second city. This was a war not of their making but one brought to them. It will be some time yet before it leaves their lives.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here