TOGETHER with his wife Hazel, the American photographer Paul Strand, then in his early 60s, visited South Uist in 1954. The couple stayed for about three months, wandering around the island photographing people and animals, landscapes and rocks.

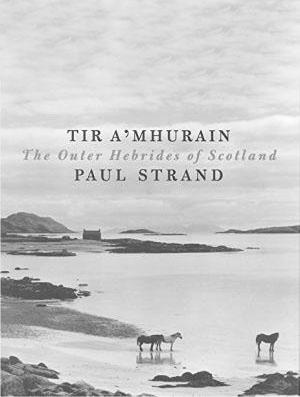

The result was Tir A’Mhuran, which was first published in 1962 and which Birlinn has republished in a manner befitting the contents. The commentary is written by the late Basil Davidson, a peripatetic journalist and sometime spy who wrote a number of books about Africa and the slave trade. What his connection was with Strand is not explained here. There is no doubt, however, that he was sympathetic to what the photographer was trying to achieve in his recording of a culture that was as fragile as the ozone layer.

In the 1950s, South Uist and Eriskay (of Whisky Galore fame), which lie between Benbecula in the north and Barra in the south, were, like their neighbours, still suffering from the 19th-century Clearances and their fallout. Crofting and fishing were life’s mainstays. Gaelic was the language commonly spoken though English was the paper means of communication. In schools, for example, children whose first language was Gaelic were taught in English. Generational poverty was a unifying force; few in these parts had much in the bank to fall back on. Another was the Free Church whose “fearful rigors”, notes Davidson, were inherited from 17th-century Geneva and were doubtless one of the reasons that Gaelic as a literary language was suppressed.

The Clearances were fresh in the minds of many of Strand’s subjects – “a bad memory, bitter in the mind, sadly retold”. Mrs Archie Macdonald, the wife of a crofter, recalled how her grandmother, then aged 12, was sent to cut the corn in a field that had been looked after by a family who had been evicted. Macdonald’s own family had escaped eviction, though they were required to move from fertile machair to a plot pockmarked with peatbogs. “In time,” writes Davidson, “this family and others like it would come to be known as ‘the rafter folk’ because they carried with them, wherever they fled, the precious rafters they would need for a new roof”.

Photographed in black and white, Strand’s subjects have a melancholy, timeless beauty. The land is by and large bleak and empty, save for a few sheep, cows and rude buildings. It is stony ground and backbreaking to cultivate. Its human inhabitants stare into Strand’s camera with an air of resignation or a half-smile of embarrassment. Many of the men wear bunnets and sport military moustaches, their complexions rough and wind-chapped. The women look younger than perhaps their years suggest, round-faced and rosy-cheeked.

The most poignant photographs are of young boys and girls who seem not to be looking into a lens but into an uncertain future. Will they be content with what their parents and grandparents have had to cope with? Or will they volunteer themselves to be cleared, to Glasgow or Edinburgh or farther afield? There is little hint in Strand’s photographs that change is on its way, that the 20th century is knocking at South Uist’s door. Horses still pull haycarts, there’s not a car to be seen, nor is there any sign of electricity pylons, and entertainment is home spun. Rock ’n’ roll, however, we learn, has newly arrived on South Uist, courtesy of the Royal Air Force and Radio Luxembourg, which delights the local girls as “an amusing alternative to strathspey and fling”.

Documenting how people survive and retain their traditions and independence in such a hostile environment was part of Strand’s mission. Born in New York, he left the US when McCarthyism was rife. He had a lifelong fascination with villages and made many studies of them and their inhabitants. Among his numerous influences were the artists Cezanne and Matisse and the photographers Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz and Walker Evans, whose images of the sharecroppers in the Alabama cotton belt during the Depression have much in common with Strand’s crofters. Also worth mentioning is German-born Bill Brandt who after the Second World War visited Skye. But whereas Strand concentrated on human beings, Brandt’s main focus of interest was the elements.

There was, of course, a political edge to Strand’s Hebridean essay. What he documented was a case of injustice. What the islanders wanted was to retain the life they had. “It is a good life,” one man told Basil Davidson. “Is a better kind of life for us than the life of the cities.”

Tir A’Mhurain: The Outer Hebrides of Scotland; by Paul Strand Birlinn: £25

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here