IN May 2015, Bernie Sanders, a 73-year-old Senator from the small, rural state of Vermont, launched an unlikely bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. Fourteen months later he conceded defeat to Hillary Clinton, but not before he had chalked up 13 million votes, 23 caucus and primary victories, and nearly 2000 pledged conference delegates, far exceeding both his own initial expectations and those of the Washington press.

Sanders’s success in the Democratic primaries should have set alarm bells ringing at the top of the Democratic party. He was a political outsider with little support on Capitol Hill. He was adept at using social media to communicate simple messages to a mass audience. He was a critic of free trade. He spoke the language of economic populism. He charged the “donor class” with “rigging the system” against middle- and low-income Americans.

Had Sanders been the Democratic nominee, he may or may not have beaten Donald Trump to the White House in November. But his remarkable rise from relative political obscurity, and the speed with which his insurgent campaign gathered pace, were early indications of just how dramatic and unpredictable the 2016 election was going to be. It was the year in which all the old rules of bourgeois politics were cast aside by an electorate increasingly appalled by traditional bourgeois politicians.

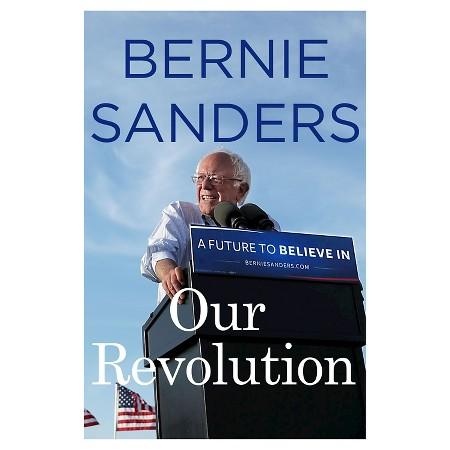

Our Revolution: A Future To Believe In is a fascinating overview of the Sanders phenomenon. It is part memoir, part campaign diary, and part manifesto. Sanders – a functional and uncomplicated writer – recalls his hardscrabble upbringing in Brooklyn as part of a Jewish immigrant family, and the radicalising effects of his time at the University of Chicago, which exposed him, at the start of the 1960s, to the reality of racism and poverty in one of America’s major urban centres.

His political career began as mayor of Vermont’s capital Burlington (population 42,000) in 1980, where he experimented with “socialism in one city”. In the 1990s, he acted as the state’s lone voice in the House of Representatives. In 2007, he was elected to the Senate. His status as an independent member of Congress taught him how to navigate a gridlocked legislature, the default setting for congressional politics in the US in the mid-90s, and to “work across the aisle”. In contrast to Jeremy Corbyn, whose tenure as Labour leader has been marked by a series of unforced media gaffes, he learned how to express socialist ideas clearly and (almost) inoffensively, in a style broadly accessible to America’s conservative political mainstream.

Before deciding to run for president he spent weeks testing the ground, travelling across the country talking to union reps, immigration reform activists and other radical voices within the Democratic coalition. He was surprised by the high levels of enthusiasm for his prospective candidacy. A groundswell of anti-Clinton resentment was already forming. Among grassroots Democrats, the party’s left-leaning base, there was no great appetite for a Clinton dynasty, and no appetite at all for a return to the policies of 90s Clintonism.

Sanders focused his pitch on Hillary Clinton’s glaring political weaknesses. He reminded people of Bill Clinton’s record in office – a record Hillary never meaningfully disavowed. Over eight years between 1992 and 2000, the so-called “New Democrats” repealed Glass-Steagall, a crucial piece of Wall Street regulation, cut welfare payments for poor families, fought efforts to legalise gay marriage, and signed NAFTA, a free trade agreement that killed thousands of American manufacturing jobs. Sanders wouldn’t let Hillary escape the legacy of the Third Way. In his eyes, she was the most prominent and unrepentant representative of a liberal establishment that had overseen what he called “the decline of the American middle class”.

IN Our Revolution, Sanders is keen to stress that he did not run any negative ads against Clinton and, to be fair, once she had secured the nomination, he embarked on an exhaustive tour of the rust belt states making the case for a Clinton presidency (or at least arguing vociferously against a Trump one). But his popularity, which was strongest among Americans under the age of 35, revealed a deep fissure on the American left. The compromises struck in the 90s by “modernising” progressive leaders – with the financial industry, the free market, and the ultra-rich – were no longer acceptable to large numbers of progressive voters.

Sanders understood that. Clinton didn’t. Clinton may have won the Democratic primaries and then, five weeks ago and by a healthy margin the national popular vote, but her refusal to deviate from a blandly triangulated message – a barely updated reiteration of Barack Obama’s “hope and change” boosterism – was fatal. It alienated just enough natural Democrats in just enough key counties to tip Trump over the threshold of victory in the electoral college.

Sanders by no means gets everything right. He acknowledges the role misogyny played in undermining Clinton’s ability to “connect” with many right-wing Americans, but probably underestimates the extent to which racism – white America’s fear of becoming a minority – helped mobilise sizeable chunks of Trump’s support. Moreover, Our Revolution contains a long list of ambitious left-wing demands, from nationalised healthcare to the abolition of student debt. The book was clearly written before Trump was elected, on the assumption Clinton would succeed Obama in the Oval Office. He can park those demands for now. For American leftists and liberal centrists alike, the next four years will be an exercise in damage limitation.

Our Revolution: A Future to Believe In by Bernie Sanders is published by Thomas Dunne Books, priced £14.99

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here