LAST week we saw how the first Jacobite Rising collapsed after the death of Bonnie Dundee at Killiecrankie in 1689, and we learned how the determined stand of the Cameronians at Dunkeld effectively ended that year’s campaign by the forces loyal to King James VII and II.

Though the defeat at Cromdale in May, 1690 really did end the first Scottish-based rising, King James was already in Ireland where he had landed with 6000 French troops.

In Ireland they still call this period the Williamite War or the War of the Two Kings. In 1690, King William himself came to conduct the campaign against James’s forces which until then had not been going well apart from the lifting of the Siege of Derry and victory at the Battle of Newtownbutler on July 28, 1689. William had become impatient with the lack of a crushing victory and his army in Ireland had suffered serious losses due to disease.

On June 14, 1690 William landed at Belfast Lough with around 36,000 troops. Ironically, given the centuries of religious strife since, part of that army was possibly paid for by Pope Innocent XI. Before his death in 1689 Innocent had allied with William in common cause against France. The claim of papal support is disputed to this day by the Vatican which wants to canonise the Blessed Innocent.

It is important to note that the war in Ireland was a minor concern in the big political picture which William viewed at the time. He wanted James out of Ireland and back in his bolthole in France for two main reasons – to finally make sure of his possession of the thrones of England and Scotland, and to free up troops for the conflict he was trying to fight on the continent where his Dutch forces and their allies fought the Nine Years War against Louis XIV’s France.

The Battle of the Boyne on July 1, 1690 (celebrated 11 days later because of the later introduction of the Gregorian calendar named after Pope Gregory XIII) ended in defeat for James who fled to France. The war in Ireland continued to the following year with the Jacobites surviving the Siege of Limerick before they were routed at the Battle of Aughtrim which featured General Hugh Mackay (the loser at Killiecrankie) fighting once more for King William.

With the Irish Jacobites mostly having fled to France, William turned his attention to Scotland briefly and made a monumental error that has damned his name to this day.

Persuaded by John Dalrymple, the Master and later 1st Earl of Stair, William introduced a loyal oath which all clan chiefs had to sign by January 1, 1692. The chiefs waited to be told by King James that they could sign and sadly, James dithered far too long. The result was that several chiefs did not sign until the last minute, and one, Alasdair Ruadh MacIain MacDonald of Glencoe, was delayed by bad weather and signed late.

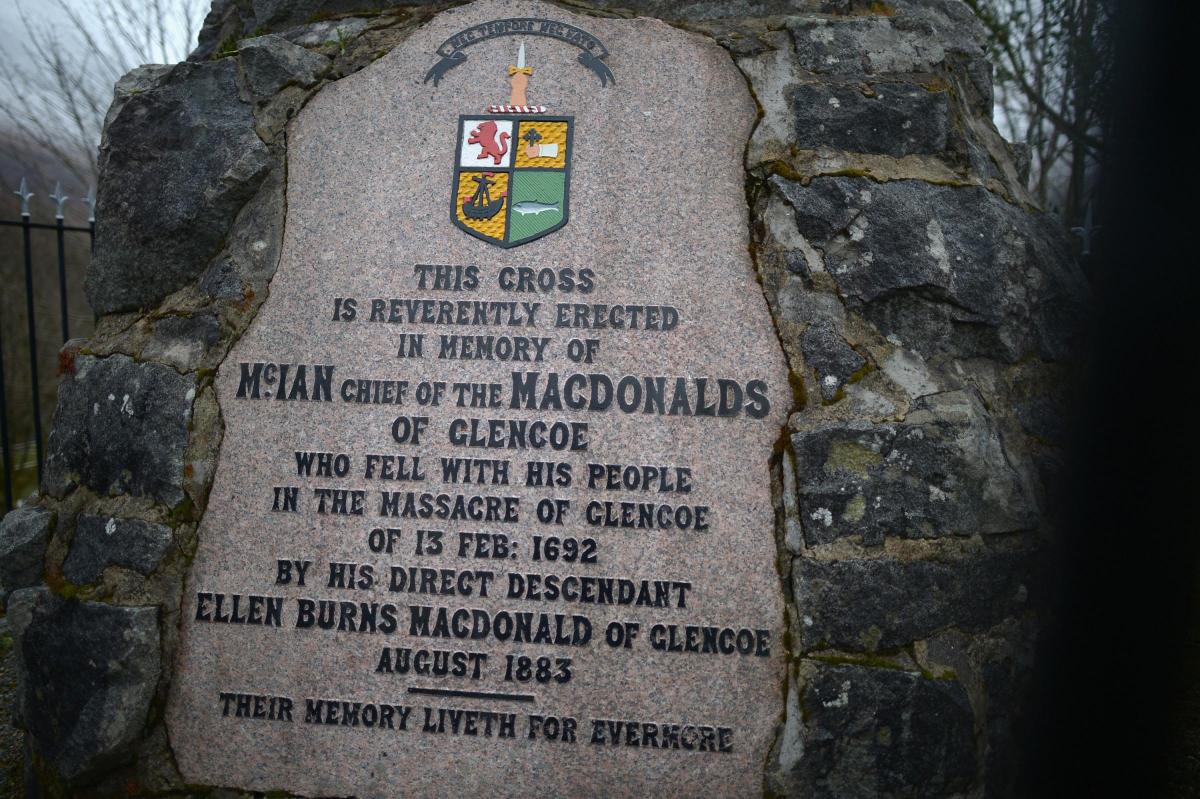

Despite pleas for clemency, Dalrymple, who was allied to Clan Campbell’s chief the Earl of Argyll, and hated the MacDonalds, got William to sign orders that the clan be “extirpated” – genocide by another word. Redcoated soldiers occupied Glencoe where they were given hospitality by the MacDonalds whose chief had been assured his loyal oath was accepted.

Though most of the soldiers were not named Campbell, it was a Campbell regiment founded by the clan chief, the Earl of Argyll, and led by Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon, which carried out the final orders from the military commander Major Robert Duncanson.

“You are hereby ordered to fall upon the Rebels, the MacDonalds of Glencoe, and put all to the sword under 70. You are to have especial care, that the Old Fox and his Sons do upon no account escape your Hands, you are to secure all the avenues that no man can escape: this you are to put in Execution at five a Clock in the Morning precisely, and by that time or very shortly after it, I’ll strive to be at you with a stronger party. If I do not come at five, you are not to tarry for me but fall on. This is by the King’s Special command, for the good and safety of the country, that these miscreants may be cut off root and branch. See that this be put in execution without Feud or Favour, else you may expect to be treated as not true to the King or Government nor a man fit to carry Commission in the King’s Service. “

Note the word “rebels” – it is clear that William’s officials and military officers still considered that a Jacobite rebellion was continuing.

On February 13, 1692 the redcoats carried out the Massacre of Glencoe. Some 38 members of the clan – men, women and children – were brutally murdered, while a similar number died of hypothermia and exposure as they fled from their homes.

The clan chief was one of the first to die, shot through the head. His wife was stripped naked and died in the snow. Their sons escaped, largely because the foul weather had stopped the full force of redcoats, half of them led by Duncanson, from being able to access the glen.

As news of the horrific massacre spread, even supporters of the Williamite cause were dismayed. Jacobite pamphleteers and politicians across Europe vented their fury at William and Mary. A cause which appeared to have died at Cromdale and Aughtrim was very much back on the agenda thanks to the bloodlust of the Master of Stair and his lack of understanding of Highlanders – it wasn’t just Highlanders who were appalled at the ‘murder under trust’ by soldiers who had been given MacDonald hospitality.

Eventually the Scottish Parliament set up an inquiry and in 1695, Dalrymple of Stair was forced to resign because he and the military had exceeded their orders. Stair was soon back in favour however, and agitating for the next big recruitment drive for the Jacobites – the Act of Union itself.

Before then, however, came two key events in Jacobite history. After Mary’s death in 1694, William ruled alone and events on the continent preoccupied him.

There had been a series of plots against him, mainly fantastical such as the so-called Ailesbury Plot, but in 1695 a plot centred on Sir John Fenwick, third baronet of that name, came to light and it was realised just how close Jacobites had come to killing William.

Fenwick, a Northumbrian Jacobite, had form for intrigue against William and Mary, having also insulted the Queen in public, before he and other Jacobites came up with a plan for a French invasion of England followed by a Jacobite rising. It came to nothing largely because the conspirators were hopeless at organisation, but their attempt to ‘kidnap’ William almost worked.

The plan was to halt William’s coach at Kew as he cross the Thames when returning from his usual hunting recreation in February, 1696, and separated from most of his escort, he would then either be kidnapped or more likely killed. One of the plotters said too much, however, and government minister John Vernon from the ruling junto got to hear of it. In mid-February the Jacobite plotters were somehow unable to get their act together, and the government acted, issuing a proclamation against them. A series of trials follow and nine Jacobites were executed.

Fenwick tried to implicate several aristocrats who he claimed were in contact with James in his French exile. They included John Churchill, the then Earl and later Duke of Marlborough – historians still argue as to whether he was a secret Jacobite at that time.

Fenwick never stood trial – he was executed after the English Parliament passed an Act of Attainder, about which we will learn more later in this series. Basically, Parliament voted to hang him for treason, but King William graciously allowed Fenwick to be beheaded, a sentence carried out at tower Hill on January 28, 1697.

William’s Government had now created martyrs and the Jacobite writers were soon creating legends. The second major event of that period was the death of King James VII and II at the French royal residence of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on September 16, 1701. He apparently had a brain haemorrhage. His son James Francis Edward was acclaimed as King of England and Scotland by Jacobites, and by the French king, Louis XIV, who is reported to have thought more of the young King James VIII and III than he did of his father.

Political machinations in Britain were now aimed at securing a Protestant heir for Queen Anne, who had ascended to the throne after William died in 1702 – he had fallen off his horse which had been confiscated from the estate of Sir John Fenwick after his execution. The horse threw William when it stepped into a mole burrow and Jacobites used to toast “the little gentleman in the black velvet coat” for bringing about the death of their mortal enemy.

Anne herself was one of the main driving forces behind the movement for a Union between Scotland and England and her principal motive was clearly the need for a Protestant heir, namely her cousin Sophia, the Electress of Hanover. James Francis Edward, who we know as the Old Pretender though that should really be Old Claimant, had to be excluded, hence the sentences near the very beginning of the Act of Union - “that all Papists and persons marrying Papists shall be excluded from and for ever incapable to inherit possess or enjoy the Imperial Crown of Great Britain and the Dominions.” Why any Catholic supports such a sectarian Union is beyond me.

The Union meant that the Jacobites had a new Prince and a new cause to fight, and a year after the Act of Union became law, a new Jacobite Rising was planned.

With France and its allies recognising James VIII and III as king, and with Louis XIV very much involved in the War of the Spanish Succession, anything which would hinder England’s efforts against the French was seen as advantageous, not least because Marlborough – with plenty Scots fighting for him - was winning battle after battle on the continent.

In Scotland, Colonel Nathaniel Hooke had been intriguing for two years among known Jacobites and by early 1708 a plan had been formed. Louis provided 6,000 troops and 300 small ships to transport them to Scotland where they would land in the Forth. Simultaneously the clans would rise in the Highlands and march south, there being very few government forces in Scotland at the time – they were fighting on the continent. James and the planners were counting on support from the ordinary people of Scotland who were known to hate the Union – martial law had been imposed since May of 1707 because of the many protests against it.

Then came one of those accidents of history that determine great events. James caught measles and the fleet had to stay in France for a fortnight to allow him to recover. When it did eventually emerge, the Royal Navy had been given two extra weeks to prepare and they chased the French fleet all the way to the Forth. Jacobites were waiting, but were too few in number, and unable to land the troops, the French fleet went home, despite James’s pleas to be put ashore. Several French vessels sank, but James made it back to France.

Numerous Jacobites were arrested, but they were all later released and eventually the 1708 Jacobite Rising fizzled out without a shot being fired on land.What might have happened had James not caught measles is a matter for speculation.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel