PURCHASING sex in Ireland became illegal this year, with proponents hailing the Criminal Law Sexual Offences Act as legislation that would transform the nation and the sex industry for the better.

But many women who offer sexual services in the Republic – along with national and international organis-ations – say the new laws have forced them to work on their own, separated from friends, networks of support and other women who help with all kinds of practical issues.

A law ostensibly promoted by campaigners as helping to end violence against women and offer rescue has left many feeling suppressed by the state, Garda and violent offenders.

Groups such as National Ugly Mugs, which facilitates information-sharing between sex workers to promote safety, have argued that the law effectively maintains criminalisation of sex workers, especially regarding its provision and loose definitions on brothels. A woman who works selling sex and has a friend answering calls, organising door calls or being on the premises for the sake of safety in numbers can be accused of brothel keeping.

International human rights and expert groups have voted on evidence that criminalisation of the purchase of sex is not only ineffective but would be harmful to the health and safety of sex workers in numerous countries. After exhaustive research, Amnesty International’s council voted in August 2015 to back decriminalisation, a move welcomed by Ireland’s sex worker advocacy groups.

This month, sex workers, charities and support groups marked International Day To End Violence Against Sex Workers, emphasising the progress – or lack of it – made by governments and labour movements in recognising the safety and rights of those involved in this work.

At the Outhouse community cafe in the heart of Dublin, I listened to Kate McGrew, a rapper, singer, writer, actress and sex worker, as she talked about a new photographic exhibition to honour the lives of people who sell sex. She told me what the show aims to achieve and how the new laws have affected the lives of those people that the legislators and some charities claim to want to save.

McGrew, 36, is the director of Sex Workers Alliance Ireland (SWAI), which was established in 2009 to promote rights, health and safety. The group has been at the forefront of the fight to ensure sex workers have a voice not only in policy making but in forcing into the public mind the forgotten fact that the safety of sex workers is paramount.

On the opening night of the show, entitled A Day in the Life, attendees commemorated the lives of 11 women who have been murdered in the Republic of Ireland while working.

McGrew explained: “The idea was how effectively you could develop and execute an idea that was not only artistic in its form and purpose – not just art with a political message but art that would have an impact on policy and transform the public mind.

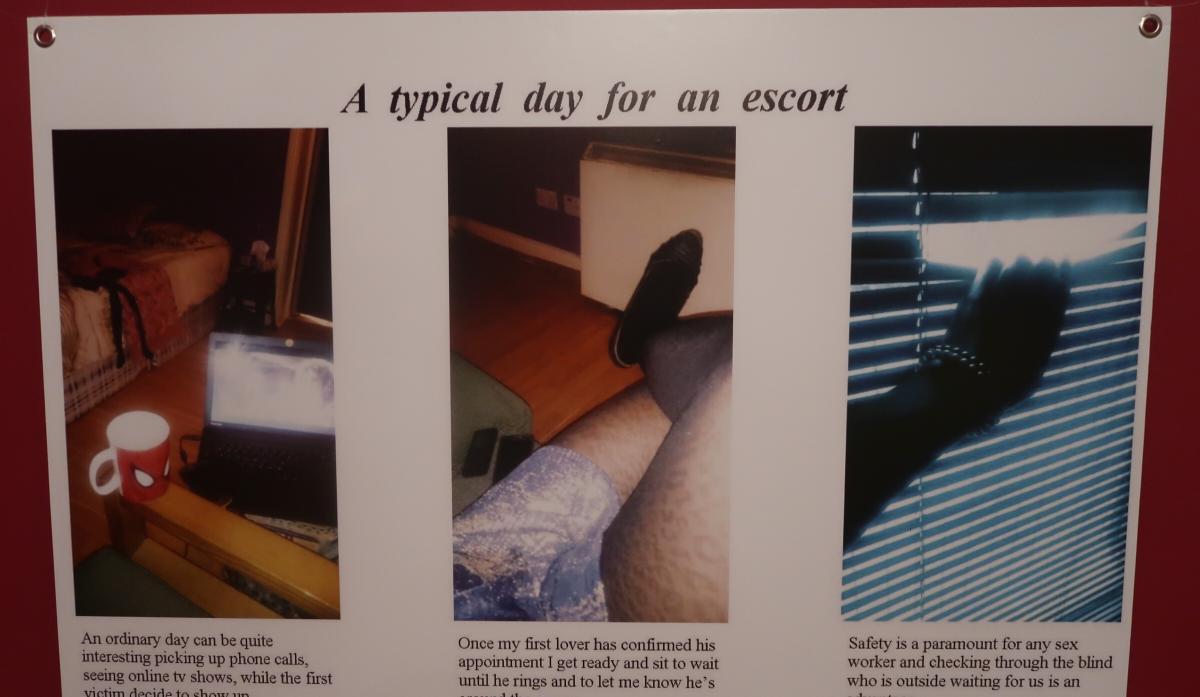

“We thought it would be a good way to convey the message we want to get across. The point is to show the breadth of voices of people who are involved and provide an intimate glimpse of this world.

“But just as we were getting under way the law was passed, the sex purchase ban had just come in, and the landscape of the industry was already changing so much. People in the community were experiencing greater risks and there were a couple of bad spates of serial violence.

“So we felt like we wanted to do something that was more in line with the kinds of conversations we were having with people in the community and something that would more directly support victims of this violence.”

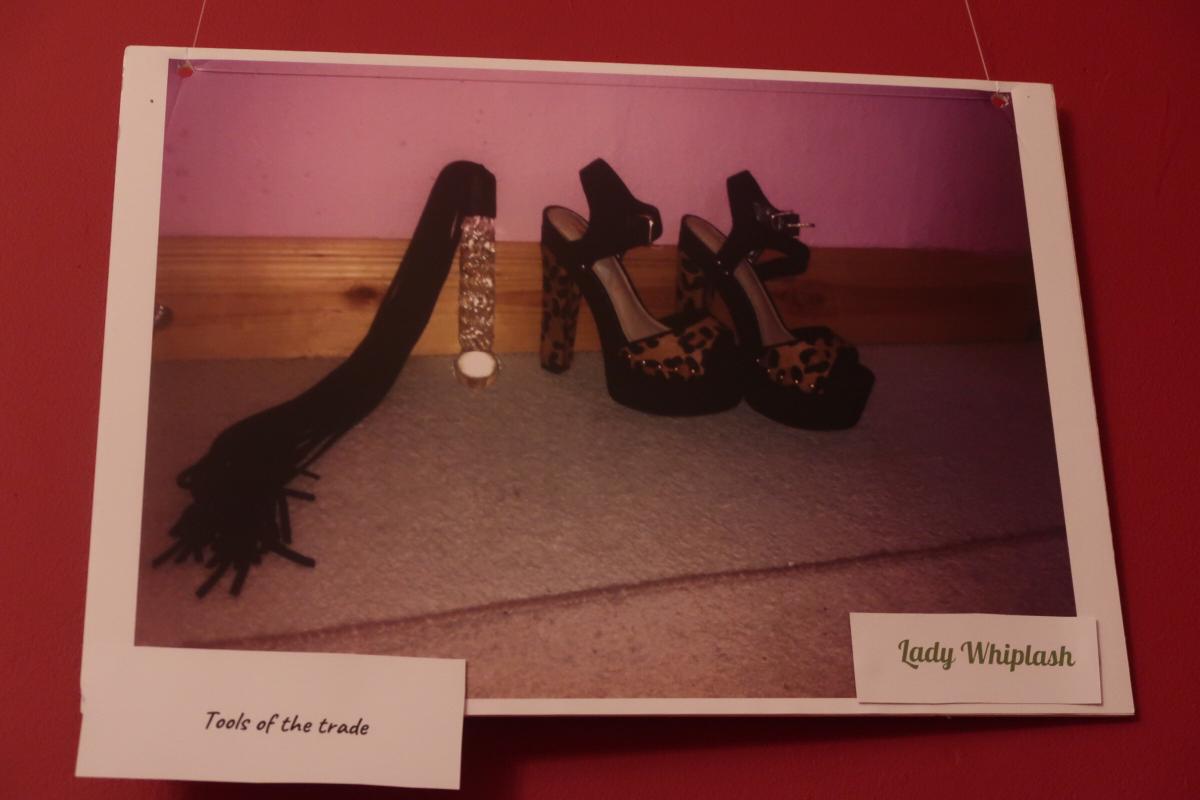

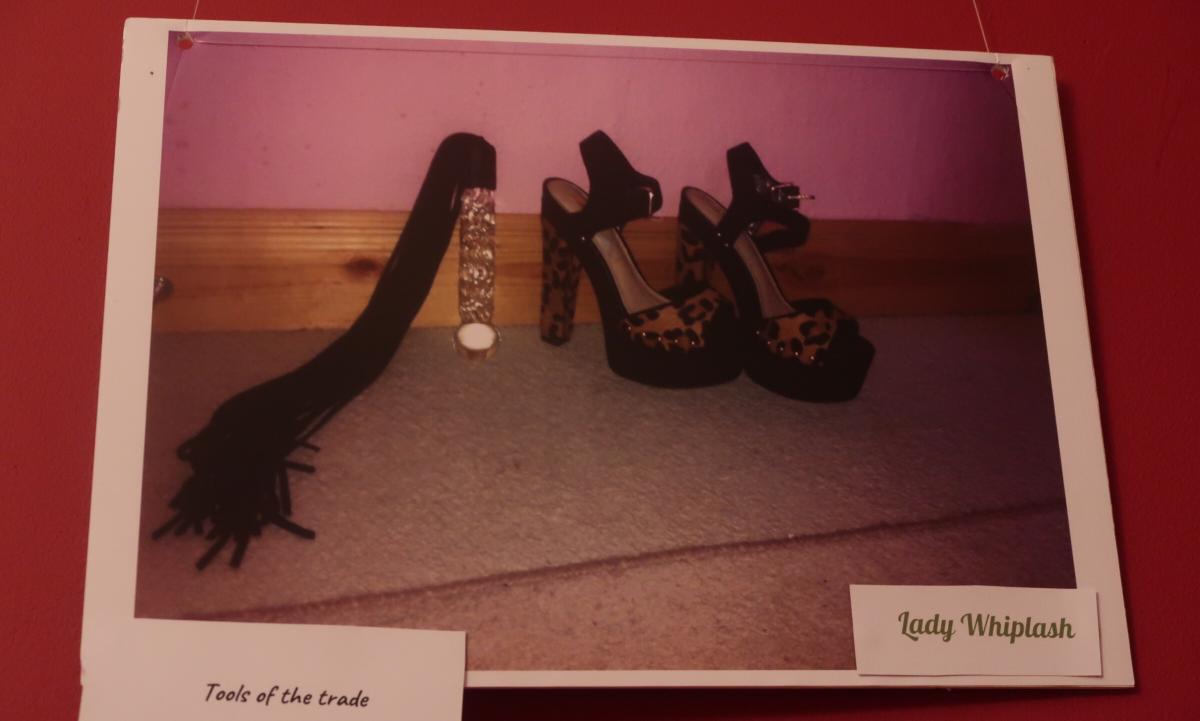

Inspired by a set of projects and workshops by the New York-based Centre of Artistic Activism, the exhibition throws the spotlight on the women and men who work in the sex industry and highlights their everyday struggles at a time when sex workers are presented to the public by politicians and the media as broken and without agency.

McGrew said: “We were people from so many different nationalities and ages but what was becoming clear was the real desire to challenge and expose misconceptions about our lives and also show the normality and the banality of our daily lives.”

Caught between the viciousness of the law and the stigma of society, the show became a way for sex workers to rediscover their voices when for so many the luxury of speaking out is impossible without the added danger of being outed. The range of expression makes the photographs a comprehensive artistic display of sex workers’ lives, a range rarely seen in our political landscape.

Erin tells how she escaped an abusive and violent husband, then struggled to support herself and two babies on benefits. Sex work offered a way to survive.

She writes: “I’m not proud of my job and do not enjoy it. But when you have mouths to feed you don’t have much choice in life.”

The human stories told through the exhibition highlight the importance for policy to be focused on alleviating the conditions that lead to violence against sex workers, and the fact that this violence goes unaddressed, often because sex workers are too afraid to come forward for fear of state harassment and deportation.

A Day in the Life, by the Sex Worker Action Group, runs until the end of the month at the Outhouse cafe in Dublin. There are plans for it to be available online in the new year.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here