TODAY is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Kristian Birkeland, the Norwegian physicist, astro-physicist, professor and explorer known as the first space scientist.

He is most famed as the first person to determine the nature of the Aurora Borealis, the Northern Lights, and for predicting the widespread existence of space plasma, the fourth state of matter after solid, liquid and gas.

WHO WAS BIRKELAND?

NOT too many people outside his native Norway know that much about this genuinely fascinating individual, who not only made space science a genuine realm of study but also invented a fertiliser, filed 60 patents of inventions and co-founded a famous Norwegian company. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize eight times – four each for chemistry and physics – though he never won it, and met a tragic and untimely end far from home in Japan.

Birkeland was born in Oslo on December 13, 1867. The city was then known as Christiana, and was part of the joint kingdoms of Sweden and Norway. He was a bright and precocious youngster, writing his first scientific thesis at the age of 18. He became fascinated by magnets as a young boy but was no geek – he used the magnets to play many a practical joke.

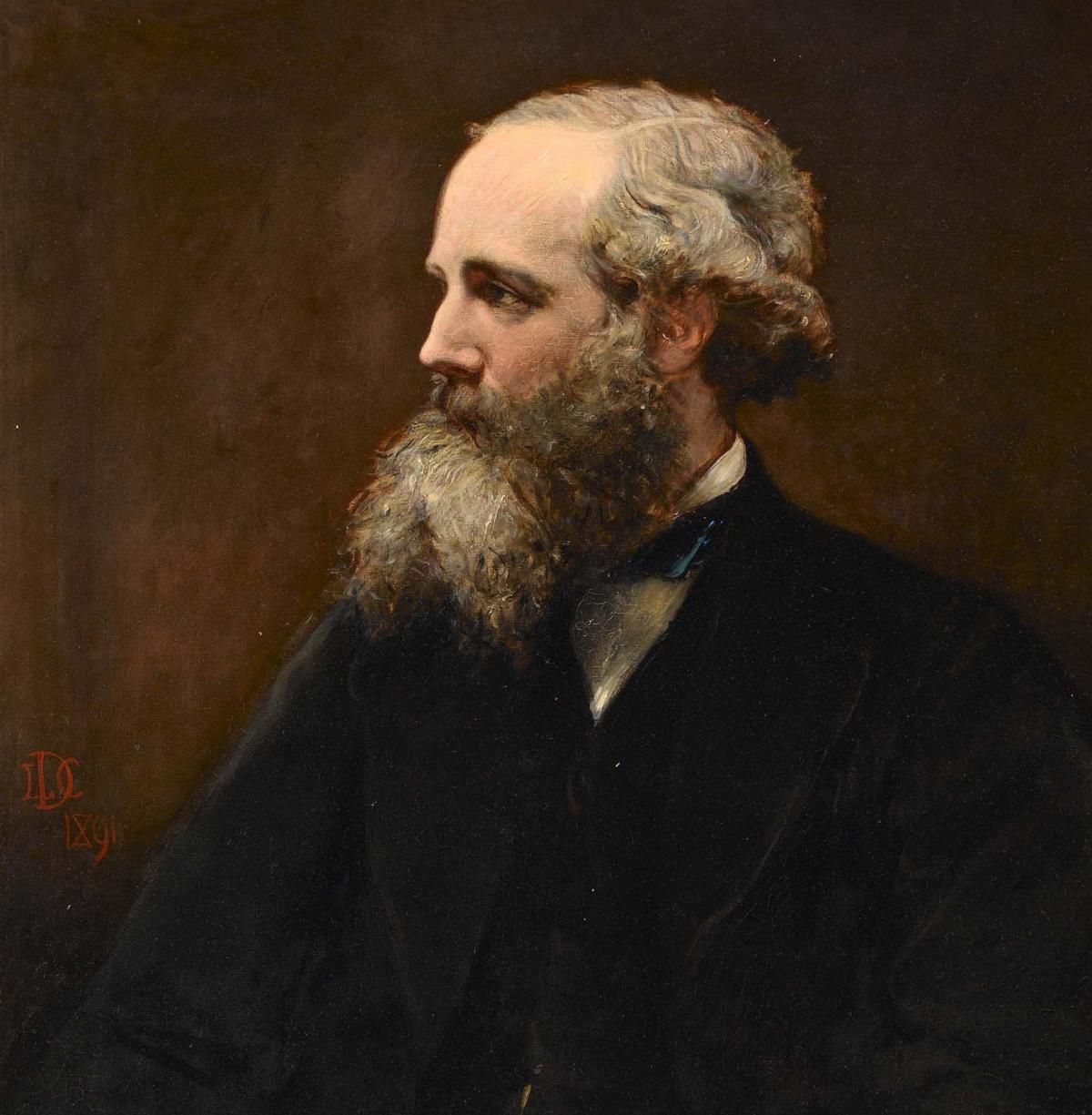

Birkeland began to study physics and particularly electro-magnetism at his home city’s university. He was inspired by one of Scotland’s most famous scientists, James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879), who formulated the theory of electro-magnetic radiation, the investigation of which was to prove a huge part of Birkeland’s career.

WHAT WAS HIS BREAKTHROUGH?

AFTER graduating from Oslo University he began to study cathode rays, which he concluded were caused by electrically charged particles that could be controlled by a magnetic field. In 1896, he began to develop a theory connecting sunspots to the Northern Lights, the Aurora Borealis – but no-one knows why he did so as he left no clues.

He then created an artificial aurora in a laboratory experiment using cathode rays, and from that he surmised that the Northern Lights could be caused by electrically charged particles from the sun.

The only way to prove his theories about the Aurora Borealis was to go and investigate them himself. He was nearly killed when his first expedition to northern Norway ended in a blizzard, but two years later in 1899 he and three companions successfully carried out magnetic measurements that proved to his satisfaction that the Aurora Borealis was several hundred kilometres above the surface and was indeed caused by particles from the sun being affected by geo-magnetic waves on Earth.

The only problem was that he couldn’t prove his theory to the mostly British scientists who were leaders in the field and disdained the Norwegian’s ideas. Even when he built a terrella, a box that simulates Earth-like magnetism, his detractors still wouldn’t accept his theory.

It was only in the 1960s that satellite observations proved Birkeland was right all along.

HE FUNDED HIS OWN RESEARCH?

AS an accidental by-product of his work with an electric gun, Birkeland teamed up with engineer Sam Eyde to patent a process for an artificial fertiliser and together they founded Norsk Hydro, which became one of Norway’s biggest companies. The Birkeland-Eyde process for fixing nitrogen from the air is named after them.

Birkeland was only interested in money to fund his research, and gradually he began to start theorising about the nature of space itself, hence the description of him being the first space scientist. He deduced that space plasma would be found throughout the solar system and beyond and he also formulated several other theories about solar light, solar wind and the origins of the sun.

HE MET A SAD END?

TRAGICALLY, Birkeland was driven only by his research. He had married Ida Charlotte Hammer, a teacher and devout Christian, in 1905. Birkeland famously gave a lecture to his students in the morning and went off to get married while still wearing his university apparel.

They had no children and were divorced in 1911, with Birkeland’s science obsessions seen as the main cause of their parting.

He began to be troubled by lack of sleep and became addicted to the barbiturate Veronal which induced paranoia in him. On a visit to Tokyo in June, 1917, he took an overdose of Veronal – whether accidental or deliberate is unknown – and died at the age of 49.

He is commemorated on the Norwegian 200 Kroner banknote.

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here