MY old maths tutor claimed that he could identify an Islay man on sight, simply from the way he walked. There was more malice than solidarity in this improbable skill. As a Muileach himself – born in Tobermory on the day the First World War began – he looked on the Ìleach with scorn, as representative of an inferior race. After a few peaty drams – and on this crucial matter he was inconsistent, conceding the Islay malts were among the masterworks of mankind – he would even demonstrate the supposed Islay gait, a kind of simian shuffle.

Slanders, of course, but the “Queen of the Hebrides” has not enjoyed an unmixed reputation over the centuries. No-one can quite determine where the name comes from. It might describe the “big buttocked” or “wide-flanked” island. It might come from a Danish princess, a giantess, who was buried there. It might mean the Isle of Law or the Other Island, or, again topographically, the Island of Halves. There’s some agreement that the definitive meaning is lost to time, leaving a residue of ambiguity that has perhaps coloured views of an island less grand but much more fertile than its neighbour Jura, less obviously storied and holy than Iona, less culturally distinct, it might seem, than Mull or Skye or the Long Island.

Angus wasn’t the only one to take a dim view of Islay and the Ìleach. Early observers found the menfolk idle and reluctant to enlist, the women dirty and undomestic. But one very quickly comes to realise that most early views were registered by literate travellers, some with missionary motives, some with metropolitan standards, and that what they might have been seeing and misinterpreting was a population living at ease close to nature. Others noted the remarkable honesty of the islanders and their unfailing hospitality, which continues to this day. But insular prejudice is a feature of the archipelago.

Angus would proudly recite an old proverb/riddle, Muileach is Ìleach is deamhan: “A Mull man, an Islay man and a devil / The three worst in Creation / The Mull man is worse than the Islay man / The Islay man is worse than the devil”. “Worse” in this case probably meaning fiercest. The point was tested at the battle of Traigh Ghruinneart in 1598, when Islay MacDonalds outwitted and outfought the Macleans, gaining victory and outlaw status in the same afternoon.

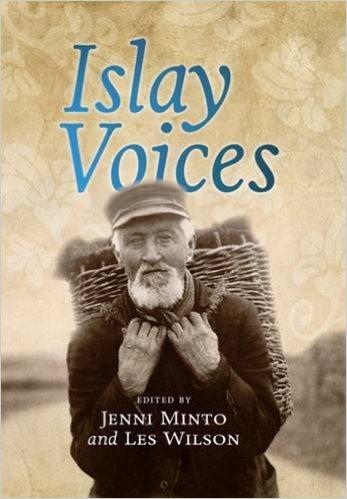

It would be easy to dismiss Islay Voices as a casual anthology, divided both chronologically and thematically, but Jenni Minto and Les Wilson have simply done what all good historians do, which is to juxtapose sources, albeit at greater length than usual, and build a narrative out of contrasting and sometimes contradictory material. It’s an elegantly paced and eminently readable account, marred only by the absence of an index and, even more frustratingly, a good map of the island.

THE human cast is dramatic and colourful. With characters as rich as Angus Òg and Godred Crovan, King of the Isles, whose burial stone (maybe) stands at Carragh Bhan, dullness is banished. But the editors also want to reposition Islay in Scottish history as an important political centre (the grand court at Finlaggan) and as a cultural hub: one of the more controversial suggestions they report is that the famous “Lewis” chessmen may actually be Islay chessmen. That’s the kind of move that gets a “!” in the chess reports.

Good though the human history is, the island itself speaks out in Islay Voices. A deceptively volatile place, which still registers seismic activity (albeit nothing like the famous earthquake of 740), it’s a paradise for geology students. And for birdwatchers, too. Gruinart attracts more peaceful visitors these days, and the knowledge that Islay is home to 80 per cent of Scotland’s choughs, pawky corvids with cardinal-red legs, brings visitors keen to tick just one species. Black-and-red birds, the famously white stones, the amber of malt, sea and sky give the island a distinctive palette, overlaid on a background of vegetation and peat.

One delightful sidebar included by Minto and Wilson is an alarming 2015 report that peat reserves on the island are likely to run out within a decade.

Apoplexy in the tasting room! Crisis meetings of the world’s malt whisky societies! Mercifully the report is dated April 1. The voices of islanders themselves gradually make themselves heard as the narrative proceeds and a more realistic impression of the island’s culture, problems and future emerges. The story peters out after the two world wars, which are perhaps as over-represented as one might expect given the proliferation of documents in wartime.

The loss of 500 American soldiers off the Mull of Oa in 1918 inspired one of the island’s most moving memorials. Islay’s strategic location meant that there was considerable military infrastructure during the Second World War, which changed the place considerably and thereafter left it in something of a backwater, only now recovering through tourism, whisky and the odd jazz festival.

Perhaps music is the only other missing element. A CD, cheap to licence and produce, might join that map and index in the second edition. And a free tot of Caol Ila or Bruichladdich. But this is gilding the lily. Islay Voices is a warm and thoughtful portrait of a magical place.

Islay Voices, edited by Jenni Minto & Les Wilson, is published by Birlinn, priced £20

Why are you making commenting on The National only available to subscribers?

We know there are thousands of National readers who want to debate, argue and go back and forth in the comments section of our stories. We’ve got the most informed readers in Scotland, asking each other the big questions about the future of our country.

Unfortunately, though, these important debates are being spoiled by a vocal minority of trolls who aren’t really interested in the issues, try to derail the conversations, register under fake names, and post vile abuse.

So that’s why we’ve decided to make the ability to comment only available to our paying subscribers. That way, all the trolls who post abuse on our website will have to pay if they want to join the debate – and risk a permanent ban from the account that they subscribe with.

The conversation will go back to what it should be about – people who care passionately about the issues, but disagree constructively on what we should do about them. Let’s get that debate started!

Callum Baird, Editor of The National

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here